Grappling with her Quest

A Conversation (or Two) with Grace Tan

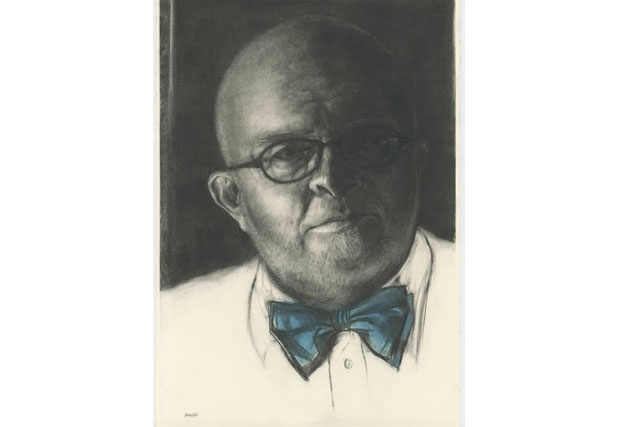

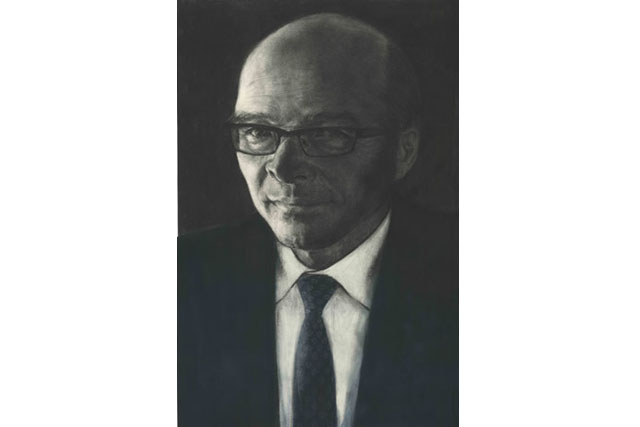

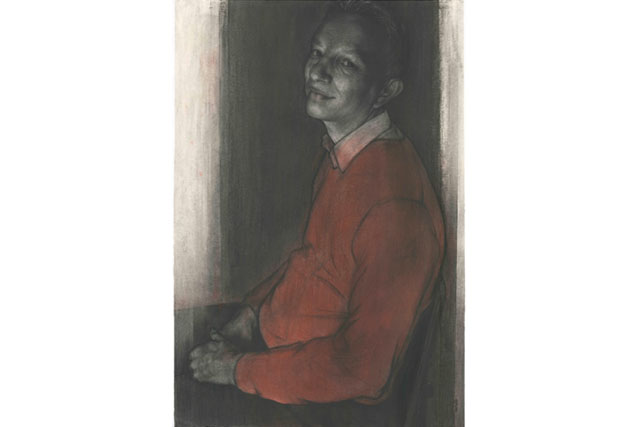

We meet a week before her exhibit “He Who Would Valiant Be” opens at the Lookout Gallery, eight charcoal portraits of men who represent for her the titular hymn by John Bunyan. Grace Tan greets me with a smile and firm handshake layered with a quiet reserve. She’s taller than I expect with shoulder-length hair and a British accent. We grab tea from The Well and move upstairs to the faculty lounge so I can hear her story above the din of atrium traffic.

Born in Hong Kong and raised in England as a third generation Christian, Grace grew up within a strong evangelical tradition. She attended two churches in London: a Chinese one led by a pastor from Beijing, and Westminster Chapel led by D. Martyn Lloyd-Jones.

Her artistic journey began at Harrow School of Art in 1966 where she did a foundation year. We don’t get too far in our conversation before she describes the early struggles she faced from the Christian community.

“When I started doing figurative work—drawing the human figure in the nude from live models—strong Christian voices around me began to speak against that, but I was too young and did not have enough wisdom in here [points to her head] to counter them.”

“Which voices in particular?” I ask.

She crosses her legs and leans back, weighing her words. “A number of Christians. They thought it was sinful to be drawing naked bodies.”

“So how did you respond?”

“I was voiceless. I had not found the sentences to adequately explain why it was so important”—she pauses and a faint smile appears on her lips—“yet.”

Despite the guilt, she continued exploring the human form while searching for words to explain it. She held her Christian responsibility of not being a stumbling block in her left hand and the compulsion to translate the human figure onto paper—the beautiful tension of skin over blood, muscle, and bone—in her right hand.

She recalls an incident in the late 1990s when she confided her struggle to a woman who seemed prayerful and understanding. The woman’s response was simply: “You must not do nude drawings.” Grace asked her, “What do you think of the Sistine Chapel and Michelangelo’s David?” The woman answered, “Well, he wasn’t a Christian. He was Catholic.”

In relaying the story to me, Grace says, “I stopped there. This person had no clue. I put her in the pigeonhole of ignorant people—no doubt she loves God and may have a crown waiting for her in heaven—but she’s nonetheless ignorant about art and had little understanding about Catholicism.”

I smile and ask if age has something to do with ignoring the voices and forging ahead with her art.

She doesn’t hesitate. “Yes, I’m running out of time. I’m sixty-five. I had better make hay while the sun shines. I have no time to fight these people, and I don’t think I’m called to give much time to defending that position anymore.”

“What do you want to do in the time you have left?”

“I have to do art. I have to let the images from here [points to her head], and here [points to her heart], and from wherever [throws her hands up] come out. Whatever I need to do with them, I shall discover when I stand before the paper or the canvas. Some people tell me, ‘It’s wonderful that you have a hobby.’ This goads me to no end, but then I think, ‘I guess it is my hobby. But in another sense, it’s totally not my hobby.’”

“It sounds like it’s your life.”

“Yes, it is. If I didn’t engage in art, I would lose my equilibrium.”

Given this answer, it’s hard to imagine the twenty-six year time span when Grace didn’t do or look at art. After completing a degree in Graphic Design from the Ontario College of Art and a BA from the University of Guelph, Grace moved back to London at twenty-four where she got married and had three children, two sons and one daughter. They moved to Hong Kong in 1981 and then to Vancouver in 1990, where she finally returned to the world of art.

When asked about her London and Hong Kong years, Grace says, “It was a different season in my life, a time devoted to caring for my family. I tried to live with a Christian purpose: to be useful. I led Bible studies and prayer groups in my home. It was not altogether wasted. I conducted myself as a fairly traditional Chinese Christian woman.”

She takes a deep breath. “But I misunderstood God. I thought he wanted me to lay down my art and so I literally wiped out my identity as someone who had this obsession inside—this magnificent obsession. After my arrival in Vancouver, through much prayer and counselling, I emerged out of some weird thinking patterns and found release from certain cultural bondages.”

Part of the recovery work in Grace’s journey involved coming to Regent in 2001. “It was the only place I knew where the tension between art and faith was being addressed by people with understanding and knowledge,” she says

At the time, various communities and churches were beginning to bless the arts and encourage artistic expression, but most of them still limited Christian art to typical religious imagery such as Jesus carrying a lamb or a nail-pierced hand. “The intention was sublime,” Grace says in recalling the latter image made out of clay at a church exhibit, “but what came out was such a visual cliché.” She adds, “The Protestant church has not cultivated a taste for art the way the Catholic church has over the centuries, and is only now catching up.”

Her best Regent moment happened in Jeremy Begbie’s summer course several years ago. A professionally trained musician and theologian, Jeremy had asked the class of artists packed into the chapel, “How many of you have felt marginalized by the church?” Every person stood up. Grace says with a smile, “That was the most wonderful moment of my life. I thought, ‘I’m not crazy’—they too have suffered from these good Christian people.”

A week after our talk, Grace had another transformational moment in Regent College’s chapel. It was the evening of Iwan Russell-Jones’ installation into the Eugene and Jan Peterson Chair in Theology and the Arts. After the ceremony, Grace found me in the atrium and grabbed my elbow. “Charlene! We need to talk again.” Her face radiated with a glow that was noticeably absent during our last conversation.

“You look like a completely different person,” I tell her when we settle into the atrium couches beneath the Lookout Gallery a few days later. “What happened?”

She throws her head back and laughs. “I was in the depths of the abyss when we talked before. I was thinking of Paul’s words in 1 Corinthians 3:12 about letting no man build except on the foundation of Jesus Christ, and if you’re building with wood, hay, and stubble, it will just get burnt up. I was questioning big time if I was building on the foundation of Jesus Christ because I realized that while my work may look good, it amounts to just wood, hay and stubble in the eternal, spiritual sense. While accomplishments are important, Jesus said rejoice not in the things you’ve done but rejoice that your names are written in heaven. [Luke 10:20] So that put things in perspective for me in the eternal sense.”

She collects her breath and takes a sip of tea before continuing.

“And then for this part where my feet are still touching the ground, Iwan’s talk gave me a lot of answers. It gave me much hope.”

“Wow, that’s huge!”

“Yes, it was huge. He answered the most important questions for me. Before the event, I had a feeling it would be significant to hear what he had to say about the artist who is a Christian or the Christian who is an artist—which comes first, I don’t know. I’m a Christian. I’m an artist. The two are separate, but the two are one.”

She tucks a strand of grey hair behind her ear. “So there I was, sitting in the third row of the chapel while Iwan was speaking, in tears because I knew that he was speaking truth—to me.”

“What part did you connect with the most?”

“He said we need to be engaging with the world and doing work that will provoke soul-searching. I was questioning whether my work was going to make any difference to anyone. I really didn’t think so.”

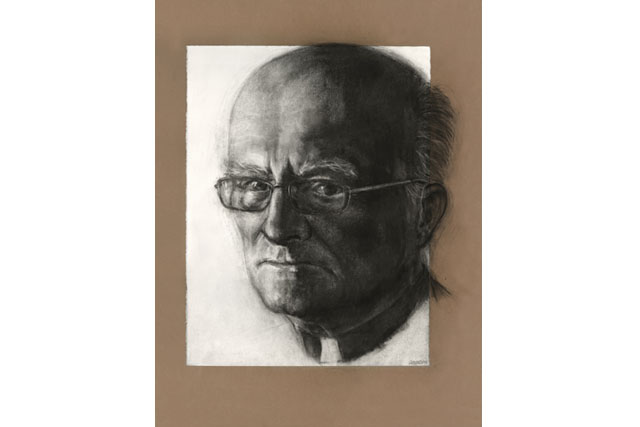

She laughs again and says when she was drawing Regent professor Loren Wilkinson, she told him, “I don’t know what I’m doing this for.” He said, “Well maybe the people who look at your work will know why you’re doing this.”

“I can’t answer for other people,” she tells me, “but my hope is that—for whatever it’s worth—whatever I do, I do honestly. If it makes a little difference to some people, if it brings them slightly closer to the truth—even a tiny piece of that big truth God wants to reveal to them—then yes, it’s good. I had to come to a point where I realized this is all just material stuff [pointing to her work in the gallery] but it isn’t just material stuff.”

I know she didn’t arrive at this point easily, and she is the first to say it is a beginning. All she knows is that she now has a little hope to ride on in her quest to understand and communicate truth. “Truth,” she repeats again softly.

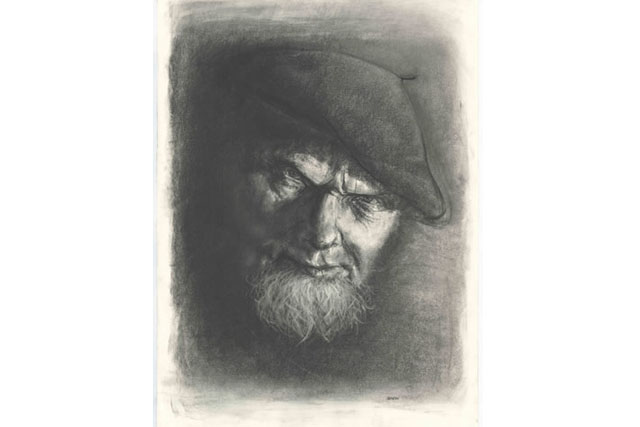

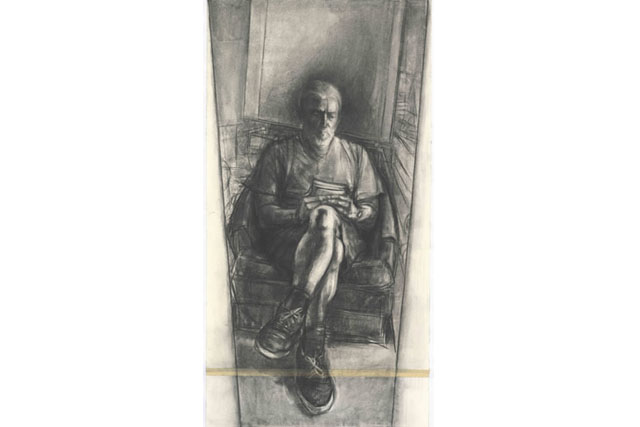

The last bit of our conversation strays into lighter things like how Loren’s face is “an artist’s dream.” She completed it in three hours whereas David Gotts’ face took her at least forty. “It is finished!” she wrote in an email to David, relieved yet absolutely exhilarated.

She tells me the essentials of a person are the eyes, mouth, and the nose that links them. “This gives the character of a person. With Loren, all of that was there within the first strike—all the marks you see are fresh, first-time marks.”

Another one of the eight men is retired Regent faculty member Dal Schindell, whom she credits for being instrumental in her journey. “He really helped to open up this quest for me. I’m still on this quest for my holy grail, and yes, I suspect that God is in this with me.”

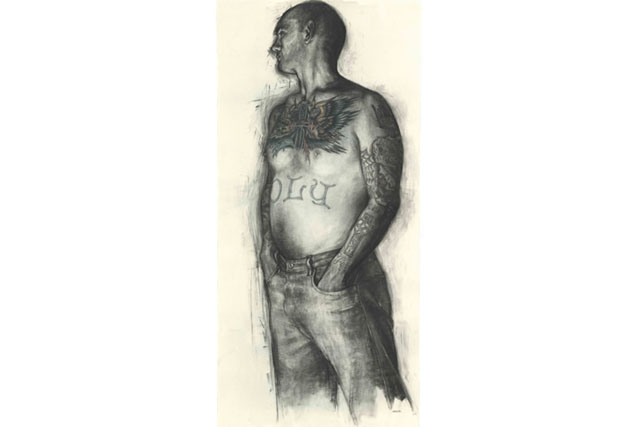

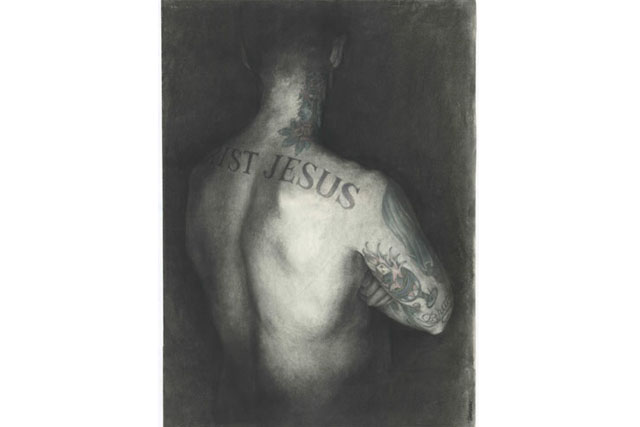

She insisted on calling the exhibit “He Who Would Valiant Be” instead of “The Valiant Men” because the former represents the idea that “we are all on a journey, longing and desiring to be valiant, mustering up courage to walk this pilgrimage, building on the foundation of Jesus Christ.”

With a glimmer in her eyes, Grace looks as if she’s pushed through the other side of a concrete wall. She can now talk about the joy in her work—a question she was reluctant to answer before.

“With all of my models, I’ve really appreciated the time they’ve spent with me. They’ve sat with me for hours, so to varying degrees, they believe in this. When a model believes in the process of making art, then just being with them is sublime.”

She resists working from photographs because doing portraits requires knowing and spending time with the person. David Robinson, a Vancouver sculptor who mentored her in 2001, posed the all-important question when she was modelling a friend’s head: “Is the Robertness of Robert there?”

I ask how she knows what the essence of each model is.

“It’s a discovery—you hit upon what makes the model unique or fascinating as a person—and it will just come out.” That’s also why drinking tea, nibbling, and chatting with her models is so crucial.

“What do you nibble on?” I ask.

“Chocolate!” she says with a giggle.

Music plays in the background while she works—great classical music and occasionally jazz. “My space is now filled with music, which was pretty much absent in my dry years,” she says.

Grace has no idea what the pose will be when the model enters her studio, but she’s watching the person the whole time, especially while setting up. Suddenly she will see it and know.

“Stop right there!” she’ll say. So they try out the pose and the majority of the time, that’s the magic moment. Her models end up becoming very good friends with her, and I’m not surprised after the three hours I’ve spent getting to know her strong yet gentle spirit.

I go home that evening and review my notes from our previous conversation. The first thing Grace told me was that she’s just a grandma pretending to be an artist. I think we both know better now.

Learn more about Grace's work on her website.