Redeeming Public Space

Iain MacPherson (MCS ‘11) came to Regent to get his MDiv and then serve God through church ministry. After his first semester, however, he switched to the marketplace concentration. Iain is now an urban planner, working in Glasgow.

Urban planner Iain MacPherson explores paths toward redeeming public space

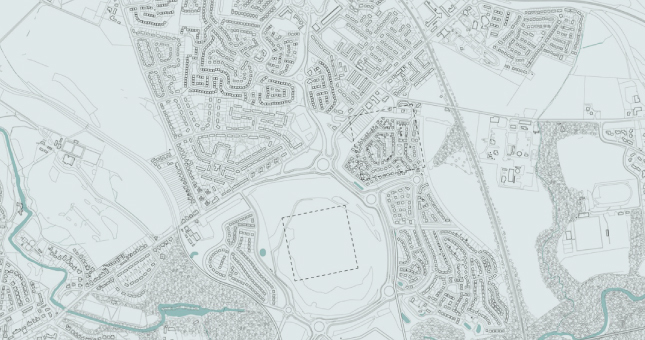

A glimpse of a courtyard surrounded by commercial buildings gives way to a pedestrianised street with pavement and sidewalk cafes. These give way in turn to a hard-landscaped square outside a public museum, a civic park, and a laneway with pubs, coffee shops, and studios. A piece of scrub land, formerly a school, now features planters built of scrap material and a community notice board. Finally, a quarter acre of grass and what feels like a quarter acre of billboard lead to a derelict concrete pad surrounded on either side by a church and some homes.

All of these spaces are found in a single journey from the centre of a city to its outskirts.

As embodied people, we have an unavoidable relationship with space, encountering and inhabiting it wherever we go. But God, too, has a relationship with space. He relates to all of human life, including our use of public spaces and the narratives they express: are they places of shalom, freedom and hope, in line with His redeeming work in the rest of creation, or do they tell a different story entirely?

There is no such thing as a public space without an embedded narrative. The way that a space has been created—its function, accessibility, ownership, and more—builds a political, social, and economic narrative that shapes and moulds the people who, by choice, chance, or necessity, use that space.

Too often, the existing narratives in these spaces fail to support freedom and hope. In my professional life as an urban planner, my aspiration is to work toward the redemption of these narratives, to seek ways of shaping public spaces with reference to the Christian narrative of hope.

This hope isn’t only for planners: all people who use public spaces, shaping and being shaped by their underlying narratives, can and should work to redeem those narratives. In order to do this, though, we need to know what we are contending with. Only in facing the narratives that shape our public spaces will we come to fully understand why those spaces, and not just those souls or activities that inhabit them, need to be redeemed.

In this article, I examine how the dominant political, economic, and social narratives undermine a people-based, community-oriented approach to public space. I also argue that the biblical narrative of hope provides us with a counter-narrative: one that invites the God of all creation to enter into and work redemptively in and through our public spaces.

Public Space—The Political Dimension

Public spaces should be shaped by a commitment to the public good, and many planners do in fact seek to develop public spaces with this goal in mind. However, planners do not have the last word on the development of public spaces: ultimate decision-making in matters involving significant change is often the responsibility of elected politicians.

At times, this reality results in the politicization of public spaces. Instead of being driven by concerns like liveability and sustainability, development is guided by other questions: What will win votes? How can we use this space as a bargaining chip?

In my hometown, for instance, an opposition party decided to turn the development of a local park into a manifesto piece. That decision led to the overturning of a public referendum, sowing discord in the local population and tainting all subsequent efforts at change in our city centre. The narrative behind the space is now driven not by a desire to see all people use the space, but by political questions: Were you on the right side? Can you use this space? What do you think of people who use it? The result has been stagnation and blame-shifting. Change is nonexistent, and freedom and hope feel very far away.

Public Space—The Economic Dimension

Economics are even more prevalent than politics in the development of public spaces. Often, decisions about the use and creation of a public space are based not on whether the change will make a space better—more beautiful, more peaceful, more green—but on whether it will reap economic benefits.

Near my previous office is an old school site. No buildings remain: the area has been vacant for so long that the natural woodland is regenerating. Local people have started using it as a community woods, with an outdoor nursery for children and multiple activities throughout the year. It serves every day as a beautiful, peaceful space where people meet their neighbours and share their lives.

Now, though, this space is under threat: the city plan has reallocated it for housing, setting the course for redevelopment. The local authority owns the site, but no investment has been made in it as it currently stands because that investment would not deliver a financial return. The value of regeneration is counted not in terms of facilitating shared community life but in hard cash. Selling and building on a vacant site delivers this. A community space does not.

There is hope for this space: the community surrounding it is well-organized and fighting the decision to sell the land. However, countless community spaces like it, along with the activities and relationships formed in those spaces, are threatened by governments that are driven by cash value rather than the social value that these places provide to the community.

Public Space—The Social Dimension

Good public space is social, generating a sense of community and providing space for human interaction with both the familiar and the unfamiliar. However, the management of that public space is often co-opted by a narrative of exclusion determining who can be part of that community.

The harshest expression of this narrative hit the headlines when space management companies began installing homeless spikes to prevent rough sleeping. There was an appropriate outcry at this frankly abhorrent practice and its underlying narrative, which says to homeless people not only “you are unwelcome,” but also “you are sub-human.”

However, while aggressive action like this is obviously unwelcoming, the same narrative of welcoming only the right type of people, with the right socio-economic status, guides the management of most public spaces.

Occupy groups and similar movements around the world have come against limitations on the use of public space as their encampments increasingly face legal challenges. Their situation demonstrates that the right to protest in public space is very closely managed and scrutinized. Anything expressing the wrong political, economic, or social agenda can be shut out of public space.

There is also a growing trend toward the commercialization of public space. Major public spaces are increasingly turned over to events such as Christmas markets and fairs. As a result, only those willing to pay have access to these spaces during festive periods: those unwilling or unable to pay are shut out.

As long as political and economic interests drive the exclusion of particular socio-economic groups from public spaces, we need to call for redemptive action that fosters greater freedom and hope.

Public Space—The Spiritual Dimension

The political, economic and social dimensions explored above inevitably impact the spiritual dimension of public space. These dominant narratives undermine the hopeful and redemptive telos that we as Christians should ultimately seek in public spaces. The questions for us, then, are: How do we imbue public spaces with a redemptive narrative? Is there hope for public space? And, most fundamentally, is public space something God cares to redeem?

Redeeming public space

In The Mission of God, Chris Wright argues that the Exodus narrative provides a grand-narrative of God’s redemptive purpose for all of his people. All of Israel’s life seemed to be shaped by a narrative embodied by Pharaoh’s rule. Politically, the Israelites had no control of their own lives; economically, their labor was exploited by the state; socially, the fabric of their society was seriously undermined; and spiritually, they were at their last, crying out to God.

However, God came into this scene and invited the Israelites into a new narrative that addressed all these aspects of their oppression: not only the spiritual, but the political, economic, and social as well. Wright puts it like this:

"In the exodus God responded to all the dimensions of Israel’s need. God’s momentous act of redemption did not merely rescue Israel from political, economic and social oppression and then leave them to their own devices to worship whom they pleased. Nor did God merely offer them spiritual comfort of hope for some brighter future in a home beyond the sky while leaving their historical condition unchanged. No, the exodus effected real change in people’s real historical situation, and at the same time called them into a real new relationship with the living God” (C. Wright, The Mission of God, 271).

If this is how God works, we can trust that he also wants to act through us to redeem the political, economic, and social aspects of our world today, including public space. As we embed ourselves in God’s redemptive narrative, we are empowered to act in a hopeful way, working to redeem public space and to meet the needs of those negatively impacted by the prevailing narratives. We live into the tension of a Kingdom that is both now and not yet.

Lesslie Newbigin argues that the church’s effort to live in continuity with the biblical story provides an alternative plausibility structure that is not abstract, but grounded in history. Our placement in the redemptive biblical story provides a basis for a real and practical hope: not a false hope for immediate wholesale socio-political change, which will be disappointed, nor hope preoccupied with a personal afterlife, which leaves the condition of our world unchanged. Our hope, as Newbigin says, “is advent rather than future. [Christ] is coming to meet us, and whatever we do – whether it is our most private prayers or our most public political action—is simply offered to him for whatever place it may have in his blessed kingdom” (Newbigin, The Gospel in a Pluralist Society, 102). In this hope, we find a framework supporting action that seeks to bring the advent of the change that will ultimately be realized in God’s coming Kingdom.

This is the framework for our redemption of public space. We recognize that change does not happen overnight, but we still seek to introduce God’s redemptive narrative into public spaces. That narrative challenges the prevailing narratives that prioritize power, money, and exclusive control. It demonstrates that public space can and should be places of freedom and hope.

This task may seem overwhelming, but it starts small. We begin by living out this redemptive narrative in the public spaces that we already occupy or control. Maybe our church owns property with some outside space; maybe we live near that contaminated concrete pad that nobody wants to use or redevelop. We can lead by living out a redemptive narrative in these spaces. As we work for their transformation, we participate in God’s hopeful work and foreshadow his coming Kingdom in the political, social, economic, and spiritual realms of our world.