Photo by Ken McAllister

Better a Creative Mess: An Interview With Dr. Cindy Aalders

How did you come to be the curator of the J. I. Packer’s papers?

I like the British word “keeper” better, though curator also works. It’s my great honour to be the guardian, steward, and Keeper of J. I. Packer’s papers.

Some years ago Dr. Packer contacted me to say he was ready to donate more of his books to the library at Regent. He’d been donating his books for years, but his increasing trouble with his eyes provoked a sober intention to donate his remaining library. He was clear the books should go to Regent. This initiated a series of conversations in which I encouraged him to also consider the value that his papers, both personal and professional, would have for the ongoing study of evangelicalism and Puritanism.

I had been his student once upon a time, but a friendship developed between us, and over the last few years it was my joy to talk with him about so many things—his practice of reading Pilgrim’s Progress every year, his love for a “bit of cheese” (which I often brought him), and his advice to me to “preach to the back of the room!”—and for me to persuade him that, yes, people would be interested, his contribution to the evangelical church was important. Eventually he agreed that his papers, alongside his books, should go to Regent.

What have you found? Is there a lot? How far back do they go?

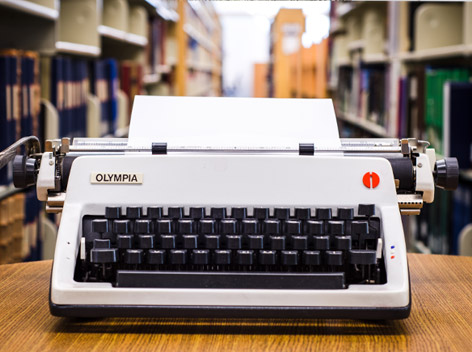

We have only now collected all of Jim’s papers and relocated them in the library, so it is too soon to give an assessment of what we have found, but I can say that there are a lot of letters, used appointment books, public lectures, teaching material, research notes, and articles written on his typewriter of choice: an old Olympia manual machine. The material dates back to at least the beginning of his preaching and teaching career. We also found Bibles, so many Bibles, tucked away in drawers and cabinets and closets. Every box we packed and closed seemed to have a Bible in it, which seems to me emblematic of the centrality of the Bible in Jim’s life and work.

What have you found that Jim kept, and didn't keep?

In a word? I’m pretty sure that Jim kept everything! He would often tell his students, “Packer by name, packer by nature,” an indication that they should expect plenty of content in his courses. The phrase took on a whole new meaning when we began to work through the papers in his home study!

How did he organize his papers?

As I was thinking about this, my friend David Robinson, who is a sessional lecturer at Regent and a former student of Dr. Packer’s, was a great help, as he remembers visiting Dr. Packer in his office at Regent and reading a motto on the wall: “Better a creative mess than tidy idleness.”

When I first entered Jim’s home study, yes, a creative mess seems the perfect phrase for what I encountered. How did he organize his papers? On first glance he seemed to put one thing on top of another—piles formed, which are chronological rather anything else. Yet even in what might appear disarray, former students attest that he always knew where to find the article he was looking for, which he was quick to loan in support of his students’ research. He kept file cabinets in which his papers are organized by subject and project. I was thrilled when Jim showed me the collection of articles he’d written over many years, organized carefully and chronologically, dating back to the fifties and earlier

A particular delight for me was finding shoeboxes filled with pages of A4 paper ripped in half and then stood on edge; each half page filled with Jim’s meticulous notes on theological subjects and/or writing projects. The pages are often written in shorthand, alongside a few words in English. The first page I examined was titled “Holiness for Dummies II,” which made me smile and think, yes, this is what we need, dear Jim.

Are there letters? Who did Jim correspond with?

There are so many letters! What I’ve been struck by in working through them is how many people wrote to Jim, from around the world, from a multitude of contexts, and as often as he heard from a former student or a colleague, he heard from someone unknown. There are multiple files labeled “letters to be answered,” some buried, I imagine, under the constant stream of correspondence. He seems to have been besieged with correspondence, and I’m sure Regent receptionists throughout the years would have stories to tell about the mail received for Jim. In fact, the mail continues to arrive.

What have you learned about Jim from what he saved? As a scholar? As an Anglican priest?

This is difficult to answer without going through the papers more carefully, but I would say that it is obvious Jim loved the Anglican Church and loved being a teacher and scholar. He was so careful with words—his notes and lecture outlines, dating back decades, are precise, meticulous, as if driven by a need for clarity. And all of this was motivated by his love for churchmen and churchwomen and love for his students.

What did you learn about Jim from working with him so closely?

It will always be one of the great privileges and pleasures in my life that I was able to be close to Jim during the last few years of his life. He was gracious to the end, humble, a gentleman such as I’ve never known. I loved to listen to him—his perfectly-formed sentences, his sometimes-surprising humour—as I knelt at his feet, surrounded by papers, and held his hand. There is something beautifully humanizing about being with a person in their final frailty.

I don’t think that he kept much that was written about him, which may speak to his humility or a disinclination to dwell on controversy. His humility is evident in the fact that his many awards and honorary degrees were found in their original packaging, on the top shelf of a closet hidden for some time by boxes and books, or tucked in the narrow space between a cabinet and the wall.

As Library Director, how do you think about making a place for this collection of work? What is the purpose of having it?

As Library Director at Regent I believe that everything we hold in our various collections should be made available for research. This is as true for modern books as for rare, antiquarian texts, as it is for archives and all else. Jim Packer played (and continues to play) a vital role in the life of Regent College, and his papers should be preserved in our institutional archives. They tell his own story, but they also tell something of Regent’s story in the first fifty years. As a historian I love to trace networks and connections, and Jim’s papers and books trace Regent connections over decades (and show how his diverse networks coincided). We see this in notes clipped to articles, colleague to colleague; in inscriptions in his books; in Regent memos that record people and events. And because everything Jim wrote and received over his long career was print, either typed or handwritten (rather than digital), it’s all right there. There is no wondering if we’ll be able to extract information from older technologies—something that worries me as both historian and librarian!

How will these papers contribute to the Allison Library’s collection of rare Puritan books?

The Puritan Project began when J. I. Packer and Jim Houston donated their personal collections of antiquarian Puritan books to the library at Regent. The collection has continued to grow through the generous support of a donor who also supports a range of activities overseen by the library. Our donor was inspired to support the Project because of the influence of Jim Packer and the Puritans on his own life. Dr. Packer made the Puritans relevant for generations of searching Christians, and so, yes, his papers will form a valuable complement to the library’s collection of rare Puritan books, providing another lens through which to understand Jim’s love for the Puritans. Jim wrote about the Puritans over the course of decades, and his papers include the many manuscripts of lectures and presentations that he gave over his long career, but they also include unpublished notes, some written in the same shorthand that we find in the margins of his books.

As a historian, what might Jim's papers tell future generations about the Protestant church and North American evangelicalism? How did being a historian, particularly one who uses and treasures personal primary sources so intensely, change how you curate and “keep”?

As a historian and now “keeper” of the Packer papers, it was a thrill to enter Jim’s study for the first time with him slowly leading the way. I looked around at a space brimming over with the good work of a long, well-lived life of service to the church and academy. As a historian, one rarely has the opportunity to encounter such papers with the author as your guide. As Jim showed me around I began to take notes and ask questions. As both historian and librarian I smiled at the sight of so much paper, some yellowed with age, some freshly arrived in the post. Everything seemed precious—not least because of my love for Jim.

I have since spent many hours in Jim’s study, most often accompanied by Lindi Lewis, as together we did the holy and poignant work of dismantling Jim’s study and removing his things (the “material culture” of his life, as my historian self would say) to bring his boxed-up writing and speaking life to Regent. Lindi has often said that the sorting process went far quicker when she worked with one of my staff rather than me. I tended to stop and read and hold up to her treasures found amongst Jim’s things: “look at this gorgeous old copy of Newton’s Cardiphonia” or “look at these notes, written in such a tiny and tight hand, what does it say?” or “wonderful, photos!” Lindi would urge me on, though sometimes she too stopped to show me something: “look at this writing contract for Fundamentalism and the Word of God [1958], written by hand in beautiful calligraphy.”

I am confident that Jim’s papers will contribute to our understanding of evangelicalism in the twentieth century, though I can’t yet say how. This contribution will require, first, an archivist to sort and organize the material and, second, interested researchers to use the collection. Both will happen in time. As a historian my impulse has been to keep everything; as librarian I will, in time, need to work with an archivist and allow them to do their work. Sometimes it can be hard being both!