Did Luther Nail It?

Iain Provan holds the Marshall Sheppard Chair of Biblical Studies at Regent College, having previously taught at London and Edinburgh universities. He is one of the world’s experts on Israelite history, and his research and teaching now span the entire Old Testament. His most recent book, published November 2017, is entitled The Reformation and the Right Reading of Scripture (Baylor University Press). This article emerges from from the research for that book.

The Reformation and the Right Reading of Scripture

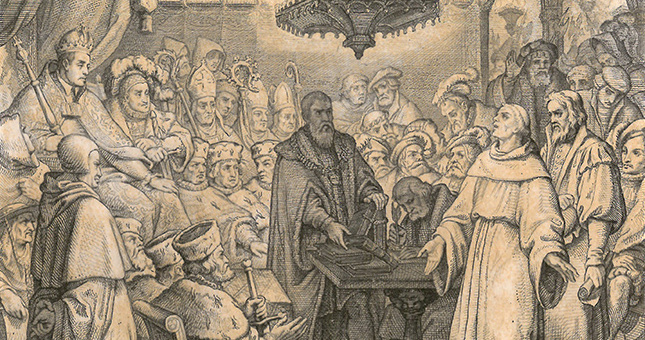

At the heart of the story of the Protestant Reformation lie questions of authority and—intrinsically connected to these—questions of biblical interpretation. These questions are nicely brought out in Martin Luther’s response to enquiries about his writings at the Diet of Worms in 1521—a kind of mediaeval parliament of many of Europe’s most powerful people. Asked whether he stood by everything he had written in the preceding years, he responded thus:

"Unless I am convinced by the testimony of the Scriptures or by clear reason (for I do not trust either in the pope or in councils alone, since it is well known that they have often erred and contradicted themselves), I am bound by the Scriptures I have quoted and my conscience is captive to the Word of God. I cannot and I will not retract anything, since it is neither safe nor right to go against conscience. May God help me. Amen."

Luther takes his stand here on “the testimony of the Scriptures” as he understands them, and it matters not that the bishop of Rome or any other bishop considers his position untenable, for they themselves are only fallible readers.

After Luther’s statement, the presiding officer at Worms condemns Luther’s refusal to recant. The officer states that an appeal to Scripture by an individual over against the church is not to be tolerated. Notorious heretics had attempted it before—exactly the company of Scripture-readers to which Luther was assigned. The Imperial Edict of Worms, issued a month after Luther’s defence, proclaims him an outlaw within the Holy Roman Empire.

It was out of the tumult of these events that there first began to emerge a “Protestant” approach to the Bible, as Luther and those who followed his lead developed their argument that Scripture, and not the bishop of Rome, should be the final authority in matters of faith and life. This argument is often referred to using the slogan sola scriptura (the Latin for “Scripture alone”).

The requirement that Christians should consult Scripture alone for guidance on doctrine and practice inevitably led on to further questions that required good answers. Thus, the introduction of sola scriptura became the seedbed for many additional central convictions of early Protestantism.

First of all: which Scripture was to be read “alone”? As to the extent of the biblical canon, Reformers like Martin Luther and John Calvin followed the lead of Christian writers in the first few centuries of the post-apostolic church—Jerome, for example—and excluded the Apocrypha. As to the text of the canon, the Reformers held that texts in their original biblical languages (mainly Hebrew and Greek) should form the basis for study of the Bible, and not the venerable Latin Vulgate. It was upon such original-language texts that Luther himself depended for the translations that ultimately came to make up his 1534 German Bible. Other vernacular original-text translations in different European languages began to appear in the same time-period. These translations were necessary, of course, since most people (then as now) could not read Hebrew or Greek. Scripture could only function in a Protestant way for most Christian believers, then, if translations in the vernacular were available.

Secondly, the Reformers believed that, equipped with Bible-translations that faithfully represented the original texts, purified now from ancient corruptions, no one possessing some rudimentary rules of reading would have undue difficulty in understanding the plain meaning of the sacred text—since as Martin Luther once put it, “[t]he Holy Spirit is the simplest writer and adviser in heaven and on earth.” Therefore (he asserts in his treatise The Bondage of the Will, in 1525), “[t]ruly it is stupid and impious, when we know that the subject matter of Scripture has all been placed in the clearest light, to call it obscure on account of a few obscure words.” That is, Scripture is “perspicuous.”

As to “rudimentary rules” of reading, thirdly, the Reformers placed enormous emphasis on the “literal sense” of the biblical text. Such opinion rejected the idea—common in the preceding medieval and patristic centuries—that other levels of hidden meaning in a text, sometimes summarized under the heading “allegorical,” were often or even normally more important than the literal sense, and indeed represented the “spiritual” sense of a text. There was widespread agreement among Reformation thinkers to the contrary—that the literal sense of Scripture, rooted in its historical context, is in fact also its spiritual sense. It is here that the “simple” sense is to be found—in what someone like Moses said and meant back in his own time. The Reformers could be strident in their opposition to allegorical reading, which they regarded as “the source of many evils” (to quote John Calvin).

In the thinking of the Reformers, however, the literal sense (fourthly) is not to be found in individual biblical texts by themselves. The “Scripture alone” that Christians are to read for guidance concerning faith and life is the whole Scripture, stretching from Genesis to Revelation, which we should receive from God as a coherent message to the church and to the world. Thus, individual texts must be read in the context of the whole unfolding covenantal story of Scripture. In particular, nothing should be inferred from a difficult or unclear passage that is not evident from other, clearer passages. This principle is often referred to as “the analogy of faith,” or “the analogy of Scripture.”

That Scripture is indeed to be “received from God” brings us to a couple of final aspects of the developing Protestant approach to the Bible in the sixteenth century that need to be emphasized. They are both connected to the notion that the Bible is the final authority in matters of faith and life. The Reformers believed, along with Christians throughout the ages before them, that the Bible is inspired by God, who speaks through it to the church and to the world; as John Chrysostom put it in the fourth century, “[t]he mouths of the inspired authors are the mouth of God.” As such, the Bible is infallible, in the sense that it does not lead its faithful readers into spiritual error, albeit that its words were penned by people long ago, and that in various ways they reflect their own times and their places.

At the same time, not every reader of the Bible does in fact receive Scripture as “from God,” even if it is perspicuous in its meaning, because understanding is not itself conviction as to truthfulness; it is possible to comprehend a text perfectly, and yet not believe a word of what it says. The work of the Holy Spirit is required in a person’s heart if he or she is to become convinced that what the text says is also true. God must speak to the individual as well as in the text. As Martin Luther puts it, “there are two kinds of clarity in Scripture, just as there are also two kinds of obscurity: one external and pertaining to the ministry of the Word, the other located in the understanding of the heart.”

We have just celebrated the five-hundredth anniversary of the Reformation. Yet in the midst of our celebration, it should not pass unnoticed that we currently find ourselves in some disagreement across our Protestant churches worldwide about whether or not we still wish to stand entirely with the Reformers in their approach to Scripture and to the Christian life. Can “Scripture alone” really speak to us clearly as from God, guiding us reliably as to what we should believe and how we should live—especially when our biblical texts are so very old? Which Scripture should we read, and how should we read it? Should I, after all, strive to read the literal sense of the text, and what does it mean to do so? Does such an objective “sense” really exist, or does not every reader simply interpret the text as seems right in his or her own eyes? What am I supposed to make of claims about infallibility and inerrancy, and do such claims require that I reject other commonly-accepted truths about the world of the past and the present (e.g., about the age of the Earth, or about the history of humanity)? Do they require that I adopt a sixteenth-century worldview?

These are only some of the questions of our time. And they add up to this question: was the Reformation a mistake? Must we now abandon its fundamental perspectives on the place of Scripture in our lives, and return to the bosom of the church(es) from which we were so unfortunately ripped all those centuries ago? Or is the only alternative to this repentance to try and find our own way in the contemporary world as best we can, founding our lives on the opinions of the latest charismatic mega-church leader or dazzling public intellectual, or on the sage advice of the television or radio personalities who possess the greatest reach, or on the basis of what “most people think,” or what is “self-evidently right,” or what I find myself most deeply to desire? Is sola gut feeling now to replace sola scriptura as our fundamental Protestant slogan?

I hope not—and I have just published a new book designed to persuade its readers otherwise. Indeed, it is designed as a serious call to a new Reformation, in line with the first. We desperately need one.