The Genius of Luther’s and Calvin’s Musical Reformation

Janet Danielson is a composer and music theorist who has taught at Simon Fraser University and at Regent College. She has composed choral, instrumental, and operatic works, and is an associate composer of the Canadian Music Centre. Her articles have been published in academic journals and she has lectured at conferences on music, philosophy, and theology.

Some myths just won’t die. Myths about music are particularly resistant to evidence or rational persuasion, perhaps because for many people the main feature of music is its style, and style is a matter of personal taste and cultural influence.

Myths about the Reformation and music centre around themes of emancipation and development.

The emancipation myth sees the Renaissance as a leap in human progress towards the liberation of the human spirit. Renaissance humanism celebrated “Man as the Measure of All Things.” Released from the repressive control of feudalism and the church, both the arts and the sciences flourished. New secular musical forms such as operas, symphonies, and chamber music emerged, demonstrating the heights attainable by unfettered human genius. In the words of distinguished musicologist Edward Lowinsky:

"One can view the evolution of vocal music in the Renaissance as one great process of emancipation: emancipation from the Gregorian chant, from the cantus firmus, from the technique of successive composition, from preexistent patterns of form and rhythm."[i]

The human development myth tends to see the church itself as an impediment. The complexity of re-Reformation sacred music did not promote musical development, because it was complex in a woefully archaic way. The Reformers, suspicious of the arts, hindered musical development even more by regressing to simple folk tunes for their congregational hymns; Luther in particular favoured tunes sung in taverns. Lutherans had to wait two centuries before J. S. Bach brought Protestant music up to the level of art again, whereas in the joyless Reformed tradition, music as an art form withered away. This myth rests on the premise that since hymns were popular, they must have been modelled on popular music. Despite its shaky logic and paucity of evidence—there are simply not enough extant examples to establish the features of a late Medieval “popular music” style [ii] –the myth rolls on:

"Congregational singing required neither literacy nor even musical talent, for the hymns in every respect were simple. … The form of these hymns was similar to that of popular songs. … The melodies thus provide us with one of the few written indications of what contemporary popular music may have sounded like."[iii]

Versions of these myths are remarkably pervasive. They can be found in internet postings, in music history textbooks and encyclopedias, and in conversations over coffee after church services. They depict a church stuck at the cultural margins, perpetually grumbling that the devil has all the good tunes.

Little of this narrative stands up to scrutiny. Renaissance humanism, for example, was an appreciation not so much of the powers of human reason as of value of the humanities—rhetoric, logic, and grammar—and of source texts, whether ancient philosophy or the Bible. Luther’s groundbreaking German translation of the Bible not only offered German speakers access to the original document of Christianity in their own language; it created a unified German language out of a multitude of dialects. The Reformation’s impact on music, I propose, was equally far-reaching. Making the Word of God “live in the hands, eyes, ears and hearts of all people”[iv] required tightening the bond between music and language, while keeping both easily and universally apprehensible. The syntax and phrasing thus imposed on music—for example the matching of eight-syllable lines to eight-beat phrases—gave music an unprecedented immediacy and expressive power, providing a template for the major genres of Western music ever since.

Polyphony Paved the Way

In Western Christianity, Gregorian chant was the universal song of worship. But in the three centuries prior to the Reformation, Gregorian chant had been elaborated into a musical art of great complexity, unlike any musical practice in the world. In physicist Geza Szamosi’s vivid formulation, the sacred music of composers such as Dufay (d. 1474) and Josquin (d. 1521) “appeared as if sounding time-spans were fitted to each other to build monumental moving structures creating exquisite and highly accurate temporal organizations.”[v] Multiple voices, each with its own independent melody, combined to create polyphony, a unified sonic whole moving forward to a concordant culmination. The exacting art of polyphony required the skills of a composer steeped in its rules and repertoire to map out the interweaving melody lines prior to live performance. Singers were trained to read or memorize these maps and to coordinate their singing via a shared common pulse. The complexity of polyphonic music led to the hiring of professional musicians rather than priests to fill the ranks of expanding cathedral choirs. Polyphony was widely condemned, even prior to the Reformation, as an egregious example of Papal extravagance.

Yet polyphony was also an enactment of Christian cosmology. It originated in a thirteenth-century Franciscan spirituality that stressed the Christian identity as that of a pilgrim and stranger, always moving through the world towards a glorious unity in Christ, the fullness of time. How did this pilgrim soul emerge from the totality of God’s being and retain its distinctive individuality while it moved through its earthly journey and finally left its body after death? Music’s non-spatial motion provided a laboratory in which the analogies of harmony and grace, the quest for perfection, and the rich plenitude of the created order could all be exemplified and explored. This is explicitly acknowledged by music theorists such as Zarlino (d. 1590):

"Thus [the ancients] held that when a consonance was reached, it was an end, a perfection toward which music strives. They did not want to repeat perfection many times so as not to satiate the ear. Their fine and useful observation confirms how true and good are the workings of wondrous nature, which does not produce identical individuals in a species but always somehow varied."[vi]

Polyphonic music beautifully models a “true and good” creation in which no two creatures are identical, yet all strive in their unique and sometimes dissonant paths toward an ultimate unity represented by the perfect musical intervals of the octave and fifth. The discovery of how harmony and discord can instantiate a beginning, a middle, and an end was an immense achievement.

Luther’s High View of Music

Martin Luther was a practical and learned musician who had great admiration for masters of polyphony such as Josquin. Luther held music to be next to the queen of the sciences, theology; and therefore greater in importance than the disciplines of arithmetic, geometry, astronomy or logic, rhetoric, and grammar. He loved polyphony, but like many on both sides of the Reformational divide, Luther realized that the incomprehensible texts of polyphonic music could compromise worship. His concern was for the common people:

"I also wish that we had as many songs as possible in the vernacular which the people could sing during Mass […] For who doubts that originally all the people sang these which now only the choir sings."[vii]

In the early 1520s, Luther invited his literary colleagues to write metrical rhymed Psalm paraphrases in German. The melodies for his own renderings of Psalm 130 (Out of Deep Anguish I Cry to Thee, O Lord, 1523), and Psalm 46 (A Mighty Fortress, 1529) were composed with great care, matching music to text in mood, in syllabic emphasis, and in phrasing. Leading authority on Luther and music Robin A. Leaver has found no evidence for the assertion that Luther drew on folk or popular song for his chorales, and much evidence to the contrary, including Luther’s clear declaration from 1524: “These songs were arranged in four or five parts to give the young […] something to wean them away from love ballads and carnal songs and to teach them something of value in their place.”[viii] Luther aimed both to replace secular song with scriptural song and to develop the musical literacy and part-singing skills of the young. with a view to placing God’s Word in the hearts of believers through music:

"We want the beautiful art of music to be properly used to serve her dear Creator and his Christians. He is thereby praised and honoured and we are made better and stronger in faith when his holy Word is impressed on our hearts by sweet music.[ix]"

Calvin’s Genevan Psalter: From Church to Field

John Calvin first heard Protestant psalm settings in 1538 in his

exile in Strasbourg. Impressed by their beneficial effect on the congregation,

he commissioned a French-language Psalter, engaging the foremost poet of the

French court, Clément Marot, to write metric versions of the Psalms. Under

Calvin’s guidance, the Genevan Psalter was finally published in 1562, with

twenty-five editions and 35,000 copies printed in its first year (twice the

actual population of Geneva). Though Calvin believed that the unity of the

church was best expressed by unison singing, the harmonized 1565 (‘Jaqui’)

version of the Genevan Psalter permanently linked the Genevan psalms with a stately

chordal or cantional style: one

melody note per syllable of text, and one chord per melody note. Like Luther,

Calvin insisted on a clear distinction between music for worship with its

“gravity and majesty,” and music for recreation:

"There must always be concern that the song be neither light nor frivolous, but have gravity and majesty, as Saint Augustine says. And thus there is a great difference between the music which one makes to entertain people at table and in their homes, and the psalms which are sung in the church in the presence of God and His angels."

Calvin also followed Luther’s lead in hoping that the psalms would be used not only in church and in the daily lives of believers, but also by the world:

"For even in our homes and in the fields it should be an incentive, and as it were an organ for praising God and lifting up our hearts to him […] But may the world be so well advised that instead of the songs that it has previously used, in part vain and frivolous, in part stupid and dull, in part foul and vile and consequently evil and harmful, it may accustom itself hereafter to sing these divine and celestial hymns with the good King David."[x]

The Genevan Psalter conspicuously achieved all that Calvin had

hoped for it. A German version, the Lobwasser Psalter, followed in 1573, and

its successive editions spread the harmonized or cantional style throughout

German-speaking Europe. Except for a handful of interruptions during the Thirty

Years’ War, the Lobwasser Psalter was reprinted every year up to 1800. Genevan

psalms were soon sung in 22 languages, as far as eastern Hungary in Europe, and

across the Atlantic to the New World.

More than two hundred years after its inception, the harmonized Genevan Psalter tradition was still thriving. In 1791, the widely-travelled composer and music critic Johann Friedrich Reichardt described his experience of church music in Zurich:

"I have never been more moved by anything than by the four-part church singing

here. The whole congregation sings the psalm melodies, to which the Reformed

are accustomed, in four parts from the music printed in the songbooks with the

verses. Frequently when I searched among the peasants in the field or in inns

for old, genuine folk songs I heard four-part psalms. He who is familiar only

with our unison church singing, usually off-pitch screaming, can scarcely

imagine the dignity and power of such four-part church singing by many hundreds

of people of all ages."[xi]

The Genevan setting of Psalm 134, known as Old Hundredth (“Praise God From Whom All Blessings Flow”), is still

regularly sung in churches. William Havergal (d. 1870) described a performance

at St. Paul’s Cathedral in London:

"At the Festival of the Sons of the Clergy in 1791, Haydn was present. The singing of Jones’s Unison Chant in D, and especially of the Old Hundredth, by not much less than six thousand voices, gave him, as he said, “the greatest pleasure he ever derived from the performance of music.”[xii]

Luther had a closer affinity to music than Calvin, yet both reformers recognized the importance of music in reforming the Church. Both grasped the importance of making melody conform to text; and both insisted that Scriptural texts be animated by rhythm, thus discovering a rich symbiosis between music and language.

A Further Contribution from Sacred Polyphony

The lasting impact of Reformation chorales and psalm-settings, then, cannot be explained—or explained away—by the Reformers’ exploitation of already-popular musical styles. But there is another feature of early Reformed music that accounts for its dignity and power, and that is the sense of each chorale being a coherent, unified whole. How is this achieved?

Sacred polyphony offered not only a sonic model of the pilgrimage of the Christian life, resounding the infinite variety of creation and its glorious culmination in a sustained concord. It also the used the technique of cantus firmus: cantus being a melody, originally a Gregorian chant, sung on long sustained notes (firmus) by the tenor (tenare, “to hold”)—which served as the reference-point for all the other vocal lines. The role of the cantus firmus is described by Pietro Aaron in 1525 in terms reminiscent of Colossians 1:17-19, where Christ is honoured as the one who holds all things together:

"The tenor being the firm and stable part, the part, that is, that holds and comprehends the whole concentus [concordance] of the harmony, the singer must judge the tone by means of this part only […] each of the added parts will be governed by the nature of the tenor."[xiii]

The stepwise motion of a Gregorian cantus firmus necessitated regular changes of harmony, yet its unbroken coherence and ever-varying melodic line flowed inexorably forward to the final note, into which all dissonances resolved. Luther himself spoke of the cantus firmus as “continuing in its course”:

"We may relish with amazement (but not understand) God’s absolute and perfect wisdom in his marvellous work of music, in which field the greatest excellence is that, while one and the same voice continues in its course, several voices play, exult, and adorn it with the most delightful gestures all round it in wondrous ways, and so to speak lead a kind of divine dance."[xiv]

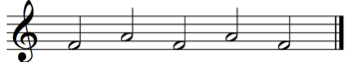

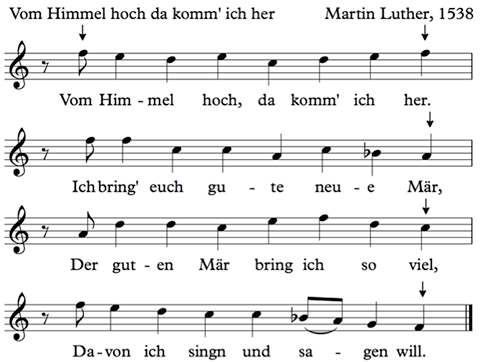

By contrast, orally transmitted folk music, like oral poetry, is typically constructed from brief repeated melody patterns on a narrow range of notes. Leaver provides us with this example, a circle song which Luther used initially for his Christmas hymn "Vom Himmel hoch, da komm’ ich her":

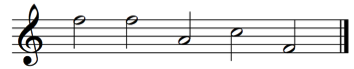

The patterns of this tune repeat within a narrow vocal range and a short four-beat time frame, but more significantly, the final tones of each phrase simply see-saw between the first and third tones of the scale, giving it a static feeling. Moving from the first tone directly to each of the final tones of the tune reveals a stagnant structural outline:

Luther replaced “Ich kumm aus fremden” with the following melody of his own composition.

The first tone of the entire melody and the final or “target” tones of each phrase of "Vom Himmel Hoch" form an elegant descent:

For Luther, musical flow was a metaphor for the Gospel, and the target tones of his chorale melodies provide a sense of progression, like a distilled cantus firmus:

"What is Law does not make progress, but what is Gospel does [that is, the Law is static but the Gospel is dynamic, or, the Law is negative and the Gospel positive]. God has preached the Gospel through music, too, as may be seen in the songs of Josquin, all of whose compositions flow freely."[xv]

Like polyphonic melodies, the melody of "Vom Himmel Hoch" moves in a rich mix of steps, skips, and leaps, “always somehow varied,” as Zarlino said. Yet these adorn a basic structural outline that both defines, and is defined by, an easily-perceived metre.

Luther recognized the Gospel in pre-Reformation polyphony. But by replacing accentless prose church Latin with metric texts set to corresponding metric tunes, he and his reformer colleagues transformed polyphony’s seamless flow into a purposeful stride. The target tones of Lutheran chorales mark off the regular time-divisions of normal speech rather than lengthy or irregular musical time-spans, and thus powerfully engage the rhythms of the human brain.[xvi] Metric psalmody was thus essential to the Reformers’ musical project.

In summation, Luther and his colleagues managed to distill the important spiritual truths resounding in sacred polyphony into a compact form that could be printed on a single page, learned with minimal music literacy, expanded into four parts, and sung as effectively by four singers as by four thousand. Most importantly, the new chorale form could exegete the Scriptural text in a way that is nearly impossible to forget. Reformation chorales and psalm settings demonstrated nothing less than a new, powerful, international musical syntax rooted and saturated in the Christian gospel of reconciliation. “To compose,” wrote Nicolas Wollick in 1501, “is nothing else indeed but the gathering together of diverse voices by various concordant [intervals] into one whole.”[xvii]

The impact of Reformation music was swift, cutting across lines of nation, class, and gender. In the mid-1540s Hubert de Paspasme wrote this account of the singing of the Protestant church in Strasbourg:

"Some Psalm of David or another prayer from the New Testament is sung, and this is done by everyone together, men as well as women, in a harmonious way […] I began to cry, not of sadness, but of joy in hearing them sing with such good heart, rendering grace to the Lord through song. When I heard the singing I could not stop myself from crying. You would not hear any one voice rise above the others; everyone has a book of music in their hands, both men and women; everyone praises the Lord."[xviii]

The dynamic new musical syntax forged by the Reformers laid the foundations for the great developments in European art music in subsequent centuries: opera, oratorio, sonata, symphony. Its “target-tone” structure was theorized and clearly described by Johannes Kepler in 1619,[xix] but then forgotten (though early twentieth-century music theorist Heinrich Schenker’s theory comes close). While it may be true that the devil has some of the good tunes, I hope this paper has demonstrated they could not possibly have originated with him. He just stole them.

Epilogue

In 1791, the year that Haydn was so taken with the singing of the “Old Hundredth” (Genevan Psalm 134) in London, he returned to Vienna and took Beethoven on as a student. He may have related to Beethoven how affected he was by the mass choral singing of the sturdy Genevan Psalm. Soon after, Beethoven began contemplating a setting of Schiller’s Ode to Joy and eventually crowned his career with its appearance his famous Ninth Symphony. The structural resemblance of Beethoven’s melody to the “Old Hundredth” is unmistakable: eight syllables per line, four lines per stanza, ranging through the octave of the fifth note of the scale, with a similar scheme of target tones. Beethoven’s Ode to Joy is now the national anthem of the European Union, but sadly, in this new role, is performed only in an instrumental arrangement without text. A unity based on politics alone, it seems, is too fragile for the potent bond of word and music forged in the Reformation.

[i] Edward Lowinsky, “Music in the Culture of the Renaissance,” Journal of the History of Ideas 15.4 (Oct. 1954): 541.

[ii]Aubrey, Elizabeth. “Reconsidering ‘High Style’ and ‘Low Style’ in Medieval Song.” Journal of Music Theory, vol. 52, no. 1, 2008, pp. 75–122. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/40607030.

[iii] Kenneth H. Marcus, “Hymnody and Hymnals in Basel, 1526-1606,” The Sixteenth Century Journal 32.3 (Autumn 2001): 725, 727.

[iv] Luther’s Works 48:356.

[v] Geza Szamosi, “Polyphonic Music and Classical Physics: The Origin of Newtonian Time,” History of Science 28.2 (June 1990): 177.

[vi] Gioseffo Zarlino, The Art of Counterpoint, translated by Guy A. Marco and Claude V. Palisca (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1968), 60.

[vii] Robin A. Leaver, Luther’s Liturgical Music: Principles and Implications (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2007), 144.

[viii]Martin Luther, “Preface to the 1524 Wittenberg Hymnal” in Vol. 53: Luther's works, Liturgy and Hymns, J. J. Pelikan, H. C. Oswald & H. T. Lehmann, Ed. (Fortress Press: Philadelphia, 1999, c1965), 315.

[ix] Luther’s Works, 53:328.

[x] John Calvin, “Preface to the 1542 Geneva Psalter,” in Leo Treitler, Strunk’s Source Readings in Music History (New York: Norton, 1998), 365, 367; italics added.

[xi] Johann Friedrich Reichardt, Musikalisches Kunstmagazin 2.5 (1791): 16; cited by Walter Blankenburg, “Church Music in Reformed Europe,” in Friedrich Blume, Protestant Church Music: A History (New York: Norton, 1974), 557.

[xii] William Henry Havergal, History of the Old Hundredth Psalm Tune, With

Specimens (New York: Mason Brothers, 1854), 46. Accessed Oct. 20, 2017.

[xiii] Pietro Aaron, “Treatise on the Nature and Recognition of All the Tones of Figured Song,” in Leo Treitler, Strunk’s Source Readings in Music History, Revised Edition (New York: Norton, 1998), 420.

[xiv] Martin Luther, Preface to the Symphoniae Iucundiae (1538), translated by Leofranc Holford-Strevens, appendix to J. Andreas Loewe, “‘Musica est Optimum’: Martin Luther’s Theory of Music,” Music & Letters 94.4 (2013), 602.

[xv] Luther, Tischreden, ed. Aurifaber 172, quoted in Leaver 2007, 101.

[xvi]Turner, Frederick, and Ernst Pöppel. “The Neural Lyre: Poetic Meter, the Brain, and Time.” Poetry, vol. 142, no. 5, 1983, pp. 277–309. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/20599567.

[xvii]Nicolas Wollick, Opus Aureum (Cologne, 1501), quoted in Ernest T. Ferand, “‘Sodaine and Unexpected’ Music in the Renaissance,” The Musical Quarterly 37.1 (Jan., 1951): 10-27; accessed: 22-10-2017.

[xviii] Daniel Trocmé-Latter, The Singing of the Strasbourg Protestants, 1523-1541 (London: Routledge, 2015), 244.

[xix] Kepler, The Harmony of the World, translated by E.J. Aiton et al. (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1997), 217-219.