J. I. Packer, John Bunyan, and Me

It was an enormous privilege to have served with Dr. Packer for a few of his many years at Regent. Our deep caring about the writings of John Bunyan and the seventeenth century. Puritans created a bond between Dr. Packer and me, and as I open my copy of one of his smallest books, The Pilgrim’s Principles: John Bunyan Revisited (St. Antholin’s Lectureship Charity Lecture, 1999) I find an inscription in his spidery handwriting, a blend of cursive and printed letters: “To Maxine Hancock, who also cares for Bunyan, from Jim Packer.”

At first it was all a bit tenuous. As a new faculty member in 1998, I was asked to give a paper to “Faculty Forum,” where Regent faculty consider each other’s ongoing academic work. My paper was titled “Folklore and Theology in the Structure and Narrative Strategies of The Pilgrim’s Progress.” There was some engaged discussion of the paper and then J. I. Packer spoke up. “Well now, this is all very interesting, but I don’t think Bunyan would have been the least bit interested in re-creating folkloric patterns. His purpose was evangelical and exhortative.”

I managed to say, “But I am not arguing from the author’s intention, just that Bunyan intuitively uses the 'three’s' of folkloric narrative structures…” Nothing more was said but it was clear that Dr. Packer would have none of a critical convention that ruled out the writer’s intention. He courteously refrained from further quashing my academic zeal in that meeting, but in the The Pilgrim’s Principles, he wrote: “Pilgrim’s Progress is studied today from many academic angles…[including] as an apotheosis of the folk tale…But I aim to review it as what Bunyan himself, the evangelist and pastor, meant it to be…—namely a teaching tool.”[1] Could it be that this sentence might be his final response to my paper? I smile to think it might be so.

I was, of course, in awe of Dr. Packer (and sorry—I still can’t call him “Jim”). Throughout my adult quest to establish a clearly-articulated and personally-owned faith, I had encountered his clear, passionate writing. His books had helped me develop a reasoned, theologically coherent and intellectually defensible position on such doctrines as the nature of scripture. Knowing God became a staple as I walked alongside new believers, encouraging them to deepen their faith—not as a set of propositions, but as an encounter with the living God. And when I returned to academic study, his Quest for Godliness, with its analysis of seventeenth-century Puritan soteriology became a steadying companion.

Yet despite my awe, soon after I arrived at Regent in 1998 I had the temerity to ask Dr. Packer if he would give a guest lecture on Calvin’s Institutes to my evening class on Bunyan and Milton. A pre-existing commitment meant that I had to be away from the college, and I guessed both that that he would have a prepared lecture he could pull out and use, and that his presence would be a bonus to the students. When I asked him to come, I said casually, “My students should know the Institutes in summary at least since, of course, Bunyan would have known them.” Dr. Packer agreed to give the lecture, but firmly corrected me—“I don’t think Bunyan would have had access to Calvin,” he said. “He was not that learned. But of course, he had Perkins and Hooker.”And with that one sentence he pointed me to a more nuanced understanding of how Bunyan gained access to a profound understanding of Reformation theology.

It was like that in so many interactions with Dr. Packer. He was a teacher above all else, or, as he liked to say, “A catechist,” with the ability to “bring from his storeroom new treasures as well as old” (Matthew 13:52). But it was not only the catechism that he taught. He also taught scholarly courtesy. Whether teaching or supervising or serving as second reader for a thesis, he took time to read student work scrupulously and to offer insightful suggestions and amendments, treating the student’s work with respect, while at the same time applying his trained and well-honed academic rigour.

He also taught respectful collegiality. Although my senior in every way, he was never patronizing. I remember with deep pleasure a time he invited me to lunch, just the two of us enjoying grilled salmon, talking about ideas, about Bunyan and seventeenth-century Puritanism, about the art of teaching.

It was Bill Reimer’s idea for Dr. Packer and me to meet with students for a “Breakfast with Bunyan,” with the two of us discussing The Pilgrim’s Progress and other works by Bunyan amidst a small “studio audience” of students munching on cinnamon buns and sipping coffee courtesy of the Bookstore and The Well. What I remember best from that conversation, (still available from Regent Audio), was—again—his speaking to me respectfully as a peer and colleague. It was all “Dr. Packer,” and “Dr. Hancock,” as we exchanged ideas about Bunyan’s biography, bibliography, and major works.

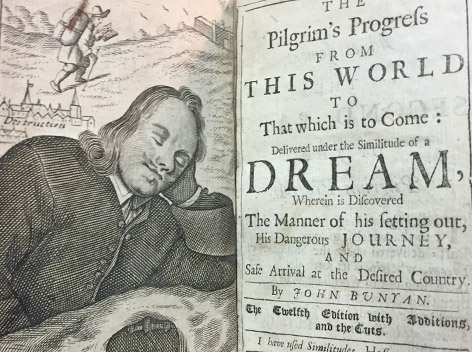

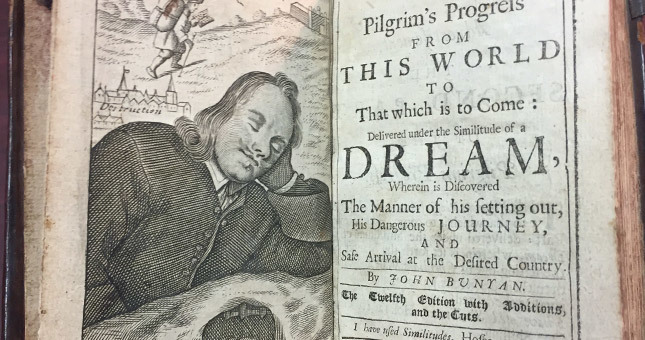

And, of course, he taught respect for the printed word, donating his collection of old Puritan books which, along with those donated by Dr. James Houston, form the core of the Houston-Packer Puritan Book collection of the Regent Library. The two old friends had recognized the worth of these books when they were being sold in British secondhand bookstores in the 1940’s and 50’s, for, as Dr. Packer often said, “pennies on the pound.”

The Puritan Book Conference in 2018, organized and chaired by Dr. Cindy Aalders, was the last time I saw Dr. Packer, by then a frail old man sitting bowed in his wheel chair, his long expressive hands, thinned almost to bone, resting on the armrests as he listened intently to the invited lectures. Once more, we saw his clarity and courtesy as he was interviewed by Cindy, his responses in those paragraph-long, compound-complex sentences of which he was the master. Crystal clear as he was intellectually, he was nonetheless nearing the edge of the River.

If, in J. I. Packer’s life, “Theology was Doxology,” so too, theology was also courtesy, with worship and praise of God lived out in courtesy to others as fellow-creatures, fellow-servants, fellow-worshippers. [Courteous: “having such manners as befit the court of a prince…” (OED) to the end, with such befitting manners and into such a court our dear Dr. Packer has now entered].

At the end of The Pilgrim’s Progress, after describing his glimpse of the joy and glory of that place, John Bunyan says wistfully, “And after that, they shut up the Gates; which when I had seen, I wished my self among them.” Oh, me too!

[1] J. I. Packer, The Pilgrim’s Principles: John Bunyan Revisited (St. Antholin’s Lectureship Charity Lecture, 1999, London: Barnard Westwood Ltd.), 12.