Jack Cusano Photography

Designed to Work, Designed to Worship

I studied architecture after a degree in math and physics because it appeared to be one of the few available professions for generalists. Finding the prospect of specialization in alternative pursuits claustrophobic, I went for it.

As a student, I became aware of the responsibility of making decisions about the built environment on behalf of others. What right do developers and designers have to create potentially manipulative spaces? Even projects with benevolent intent such as public housing in Europe and America has ended up as destructive to their users. To a conscientious designer, the assumptions implied in making decisions that will be formative to users are almost immobilizing in their intensity. It appeared to me that the nature of being human was fundamental to this discussion and that one could only proceed in this profession with a robust and convincing understanding of what it means to be human.

At this time, I came in contact with Francis Schaeffer and Hans Rookmaaker who convinced me to build environments that remind users they are created in the image of God. This thought has immediate implications in terms of materials and scale. The idea that humans are made for relationship implies that I have a right, and maybe even a duty, to use this criterion both in the design and operation of my practice. Consequently, much of my business life and design work has had the intention of fostering relationships and community.

For example, in 1988 when the original Regent building was designed, I understood education to be facilitated as a learning community as opposed to just the transfer of information in classrooms. I was able to introduce the concept of the atrium space which Clive Grout, the architect of record, skillfully incorporated into the project. The atrium was intended to be an open space that facilitated the meeting and interacting of members of the College. For instance, you can’t really get anywhere in the building without passing through the atrium first. (see photo 1)

Church Architecture

So what about the practice of designing churches, of which I have significant experience? I have understood my role to facilitate and collaborate with congregations to achieve buildings appropriate to their needs and ministry requirements. I have found that once the main design parameters have been established, projects take on a life of their own and my role becomes something of a spectator.

A majority of my clients have been part of evangelical traditions that seem to have an aesthetic that leans toward the utilitarian. All congregations have a liturgy, meaning the way in which the service is conducted. Traditional liturgies tend toward participation and the “contemporary” ones lend themselves to entertainment. My ideas about the church as a worshipping community have sometimes been frustrated by requirements for the dominance of the pulpit and the prevailing definition of performance music as worship. Nevertheless, I have felt led to introduce a few ideas to influence these attitudes:

- Wherever possible, to encourage the idea of beauty as intrinsic to God's character.

- Enhance the sense of community in the congregation. For example, I have refused to design balconies in churches because they tend to separate the congregation into participants and spectators. One of my projects, Centre Street Church in Calgary, seats 2,300 people on one level in the main auditorium with no balcony. In St. Michael's Catholic Community, the seating is configured so that you can see the faces of about two thirds of the congregation from any seat in the room.

- Configure foyers or narthexes so that people meet and encounter one another.

- Use materials honestly, avoiding artificial materials that imitate natural materials. For instance, I try to avoid plastics that are made to look like wood.

- Practice stewardship in the efficient use of materials, particularly in structures. The popular semicircular sanctuary layout in many evangelical churches uses a radial structural arrangement that requires significantly more and larger structural members than a rectilinear one of the same size. This arrangement also implies a long and narrow foyer that wraps around the sanctuary, discouraging congregation members to encounter one another.

Some examples of these ideas in application come to mind:

Centre Street Church

Centre Street Church in Calgary afforded the opportunity to incorporate baptism into a large contemporary facility. The foyer is designed so that most users will walk through it to reach any part of the building and become aware of other members of the community. (see photo 2) The idea of locating the baptistry in the foyer was borrowed to some extent from older liturgical traditions. The baptistry includes a pool and a two-story waterfall. The engineering and design were a significant challenge but it was worth giving baptism a significant presence in the building. (see photo 3)

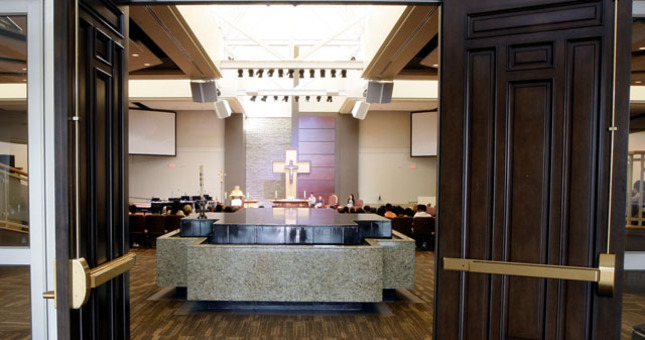

St. Michael Catholic Community

Recently, I have designed two churches from the Catholic and Orthodox traditions that are oriented to symbol and metaphor in a way that most commissions are not. I have learned that it is possible for the building to actually “speak” the message of the liturgical story, which is the gospel.

The baptismal font at St. Michael Catholic Community in Calgary is a particular detail in context of a larger project intentionally designed around the liturgy. (see photo 4) The font is located at the entrance to the nave because it is the rite of initiation into the Christian community. The font is a virtual pool that continuously wells up and spills over as an expression that God's grace is abundant and active. In the case of adult candidates, baptisms are held on the Saturday evening of the Easter Vigil. Candidates enter from the outside in simple robes, go down into the water, and identify with Jesus in his death. The font has a transformational agenda as the newly baptized leave the font on the other end as new creatures and participants in Christ's resurrection. They are anointed with the oil of charisma to receive the Holy Spirit, and then they participate in the Eucharist in the community of redeemed ones. The nave is designed so it is not possible to enter or leave it without passing the baptismal font—a constant reminder not only of individual baptismal vows and personal salvation stories, but also of redemption, transformation, and the receiving of grace.

On this project, we introduced a columbarium—a place, according to their website, that “offers a consecrated and sacred space where the cremated remains of deceased loved ones may rest in perpetuity, awaiting the return of our Lord.” (see photo 5) In contrast to traditional crypts, this area is flooded with natural daylight and has been designed to accommodate artwork based on a resurrection theme. The intent was to express the idea that the “dead in Christ” constitute the church as well as the current users of the building.

St. Mina Coptic Orthodox Church

From the Orthodox tradition, St. Mina Coptic Orthodox Church is designed as a sort of model of the universe with many symbolic aspects, both on the exterior and in the interior. (see photo 6) The liturgical story depends on the building as the context for God's action in heaven and on earth. The icons and relics introduce the narrative of the personae they represent.

The area behind the iconostasis is understood to be a corner of heaven because of the real presence of the Lord in the consecrated bread and wine. The space occupied by the congregation is part of the world we presently live in. The Bible is kept on the main altar behind the iconostasis. In most orthodox traditions when it is read, it is brought out to the middle of the people, a deliberate enactment of “the Word becoming flesh and dwelling among us.” This project is the subject of an upcoming display in the Lookout Gallery at Regent from May 15-June 26.

There is a great deal to be learned by reflecting on the role of God's kingdom in the process of designing environments in which humans can live, work, and worship in all their astonishing variety.