When Christianity Becomes a Brand

Veronika Klaptocz is Senior Writer and Editor at Regent College, and the Managing Editor of The Regent World.

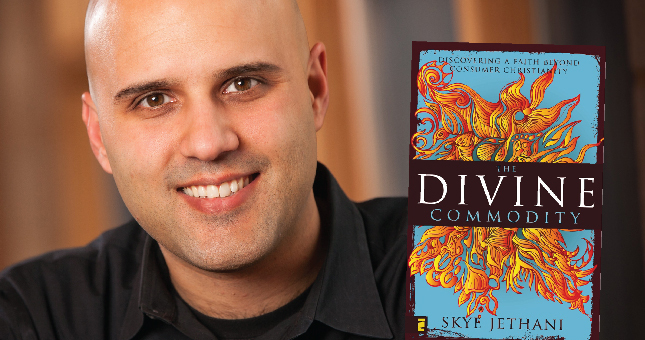

A Conversation with Skye Jethani

In his 2009 book, The Divine Commodity: Discovering a Faith Beyond Consumer Christianity, Skye Jethani identified consumerism—and not atheism, or postmodernism, or hedonism—as posing the greatest threat to North American Christianity. In a phone interview, we asked him to elaborate on the themes of his prophetic book.

In The Divine Commodity, you make a distinction between consumption and consumerism. Can you define these terms for us and explain how they differ?

Consumption is a behaviour. We are contingent creatures, which means that we must consume things in order to survive. Things like air and water and food and clothing and shelter. So my critique has nothing really to do with consumption.

My bigger concern is consumerism. The difference is that consumerism is a worldview. It’s a way of perceiving oneself and one's place within the world. What consumerism tells us is that our identity and our significance are constructed through our acts of consumption. It's a way of perceiving the value of other people, the value of God, our very purpose in this world. And the way we've been shaped by a consumeristic worldview has impacted our perception of our faith, and God, the church, and his mission.

Part of the danger is that we don't realize just how much our worldview is shaped by consumerism, and the subtle ways in which it infiltrates our behaviours.

Yes, in the years that I've been around this conversation, a lot of people will talk about the threat of postmodernism, or the threat of modernity, hedonism, all these isms, atheism. And very few people in the church are talking about consumerism as being the dominant worldview that shapes the perceptions of everyone today. So that's the main reason I wrote this book, and why I think it's so important to talk about. It's the water we're swimming in that nobody's acknowledging.

Can you give me some examples of how consumerism has crept into our churches and our worship practices, and how it has affected our relationship with God?

One of the core components of consumerism is commodification. That's an economic term, but I think it applies far beyond just economics. What commodification says is that value's not found in something's inherent quality, but in what it can be traded for, or exchanged for.

So in consumerism, we've come to believe that nothing has inherent value any more. And that a thing or a person's value is simply to be found in its usefulness, or what it can be traded for, or what can be gained from it. So when we take that into other areas of our life, and see how that impacts our faith and the way we view other people, a human being is no longer valuable apart from its usefulness. So an unborn child is no longer useful and can be thrown out. An elderly person, a handicapped person, somebody who has a different skillset that's no longer valuable—can just be discarded. The fact that human trafficking and slavery [are so prevalent]—27 million people in the world are enslaved today, more than any other time in history— that's a reflection of viewing human beings as commodities, just tools to be used.

And then we carry that same attitude toward our faith in God. We do the same thing. We believe that God, and his value, is simply to be found in his usefulness. For decades now, people have been upset about the biblical illiteracy that is prevalent in North America. And yet we have more Bibles and more Bible schools and more churches and Christian radio stations and resources than any Christians who've ever lived in history. Yet rates of biblical illiteracy, even among Christians, are going up and up and up. And I think it's because we've made God into a commodity where we don't really care about what he did thousands of years ago, where we don't really care about the theology or the biblical context that gives him value and meaning. We simply want to know, "how can I use God to make my life better right now?"

Are there particular biblical texts or stories that have shaped your thinking on consumerism?

One that comes to mind is Psalm 27, where David says that he has one desire and that is to dwell all the days of his life in the house of the Lord, so that he might gaze upon the beauty of the Lord. This verse captures that David understood that God has inherent value.

The other one I go to is Luke 15, the story of the Prodigal Son. I think that story captures wonderfully an image of God's relationship with us and our relationship with him, in which the most important thing is not using the other person but being with the other person. At the beginning of the story, the younger son just wants his father's wealth so he can squander it on his selfish desires. There's a case of simply wanting to use God to achieve my desires, that's making God into a commodity. But by the end of the story you see the Father embracing the younger son, and you also see him going after his older son. And he says, all these years you've been with me, now your brother's back, and it's time to celebrate. And the emphasis there, in the Father's heart, is having his children with him.

So what often happens [is that] we come out of a consumer posture, and believe that we're supposed to just use God to achieve our desires. But then, often what the church communicates is all God really cares about is using you to accomplish his mission or accomplish his desires. And both of those really stem from a consumeristic idea that God exists to be used and we exist to be used. But what you get in Scripture is a far deeper calling of intimacy in God, of the inherent value of God. And then discovering that he believes we have inherent value as well, and he's not really interested in using us but he desires us, wants to be in unity with us, and reconciled to us.

In your book, you critique how Christianity can become a brand among others, and Jesus can become a label. We consume all these Christian products – the books, the music, the conferences, without questioning our motivations. Can you tell us more about that?

Philosophers have noted that in a consumer society, the way that you construct your identity is through the brands that you purchase and display. So when you're buying a car, it's not merely about finding a vehicle that can transport you, it's also about the values and identity associated with the brand – Mercedes or Honda or whatever you're purchasing. Or the clothes you wear and the brands you display. A number of decades ago, a weird thing happened where we started putting the labels on the outside of our clothing so people could see what brand we were wearing because we wanted to be associated with it.

And that mentality then gets carried into religious belief. So we display externally that we are a Christian by the jewelry we wear, or the t-shirt, or the bumper sticker, or the music. The problem is similar to what Paul faced in the first century BC with circumcision. Circumcision was really the original religious brand. It’s an external symbol of one's spiritual identity. And people came to believe that if you're circumcised, you're a Jew; if you're circumcised, you belong to God's people; if you're circumcised, then you are all good to go. And Paul repeatedly said no, it's not about circumcision, it's about faith working through love. What Paul's concerned about is not what external symbols you're displaying but what's going on in your heart. Do you desire God, do you have faith in him, are you trusting him, and is that faith and trust manifested in love towards God and towards others. And that's why he called people not to be circumcised, to put those external symbols aside and seek the deeper inner life.

Now strictly speaking, Paul was not against circumcision. He had his associate Timothy circumcised for a very practical reason. And if Paul was speaking to us today, he wouldn't say that all Jesus-branded merchandise is inherently evil or wrong, it isn't. But the danger is that we can fill our lives with so much of those external brands and we can present to the world this façade of Christianity but internally, the faith, the hope, the love that we're called to have isn't really developed. And I think a lot of that is inoculating people to a genuine faith because they think they're Christian because they have all of the trappings and symbols of Christianity around them, but they're not actually experiencing that inner life of communion with God. So that's really the danger of branding, it's not that it's inherently evil but that it distracts us from what we're truly called to.

So what are some of the remedies or solutions that you propose in your book?

In each chapter, I look at a different spiritual discipline as a way of reforming our thinking and way of living. So when it comes to branding, one of the things I propose is, number one, as Paul did, put aside those external religious brands, don't merely display them externally. Then, incorporate into your life the spiritual discipline of serving others. In service, manifest the love of God to others from your life, not just from your t-shirts or your bumper stickers.

When it comes to not valuing God merely for his usefulness, it means worshipping and being part of a community that isn't just presenting God as a useful tool to help you through your life, but surrendering your desires, taking up your cross, and engaging in worship for its own sake, for God's own sake.

Another one is the Sabbath—ceasing from my work to recognize that my value comes from something other than my usefulness, other than from what I can accomplish in the world. When I don’t work, when I stop my external engagement for a day or for a season, I'm reminded that I'm inherently valuable to God, not just useful to him.

Your book came out in 2009. Do you think it's had some impact? Have you had conversations that suggest people are taking some of your ideas to heart and putting them into action?

Yes, and no. It hasn't been a bestselling book. But as I get around and talk about these ideas, the reaction I get more often than anything else is, "I have felt that way for a long time, but your book or your talk articulated it in a way I hadn't thought of before." I think a lot of people suspect that there's some barrier in the North American church, some way of operating that isn't quite right, but they haven't been able to articulate it. That's what the book tries to do. Here's what you've been experiencing and here's why it doesn't seem quite right.

The other thing I'm finding more and more is that among younger people, there's a greater cynicism towards our consumer culture than there was for the baby boomer generation. In their cynicism, they're very much turned off highly polished, programmed, branded churches that are acting as if they're selling a product. They're looking for what is authentic—they're looking for that raw, honest engagement with God and one another. And I'm encouraged by that. But it's important to remember that consumerist ideas don't just infect mega-churches, don't just infect baby boomers—anybody living in the North American context, and beyond, is going to be deeply shaped by this in their approach to faith. So we can't just point the finger and say they're the ones who are affected by consumerism and we're not. We're all equally affected, it's just being manifested very differently.

That search for authenticity is key, isn't it? What about Christian organizations, which are ministries, but also need to respond to market forces? How do they navigate the realms of marketing and advertising, and the pressures to compete with other ministries, without compromising their identities or ethics?

And that's a really good point. I don't want anyone to assume that I think marketing or branding or consumer capitalism are inherently evil. They're not. They're just the systems we find ourselves in. What's dangerous is when we are unaware of how living in those settings impacts the way we engage our faith. So the answer is not to escape from those systems and completely retreat: I don't think that's possible. The solution is not to fight the system and say, well, consumer capitalism is wrong, we need to change it: that's not going to work either. The solution is to have our imaginations awakened to the fact that the kingdom of God operates differently. And we need to be aware of the environment we are in, so that when we gather together as sisters and brothers in Christ, when we gather for worship and for study of Scripture and for sacrament and discipleship, we can talk about the realities of the environment we're in, and encourage one another toward a different vision and way of life for ourselves in Christ.

The biggest problem I have with all of these issues is that we're just not talking about them in the church. And if we don't talk about them and acknowledge their reality, then we give them far too much power and influence.