We Are Still Near the Beginning

A Conversation with Wendell Berry

On November 8, 2014, Regent alumnus Chad Wriglesworth sat down with prolific author Wendell Berry to discuss work, sustainability, and eternity. The conversation, which took place at the South Atlantic Modern Language Association Conference in Atlanta, Georgia, was first published in the Spring 2015 edition of CRUX, a Quarterly Journal of Christian Thought and Opinion published by Regent College. We are grateful to Wendell Berry, Chad Wriglesworth and CRUX Senior Editor Julie Lane-Gay for graciously permitting the distribution of this exclusive article to the broader Regent community. For more information or to subscribe to CRUX, click here.

CW: Wendell Berry, thank you for being here with us this morning. This is truly a great pleasure for me, and I’m sure for many people in this room.

While working on Distant Neighbors, I stumbled across many things about your life and work that I now realize are quite important to who you are and what you do. So I thought we might begin by talking about the relationship between work and sustainability. For example, you grew up in the 1940s and ’50s, in a household where matters of economic sustainability were of central importance. I’m thinking here specifically about the work your father did with the Burley Tobacco Growers Cooperative, which came into existence under the New Deal. Could you tell us a little bit about the program—what it stood for, and what happened to it?

WB: Well, let me begin by saying that I think the separation between people and land is tragic. Let me give you an example that doesn’t have anything to do with the tobacco program.

Fifty-one years ago, Harry Caudill published a book called Night Comes to the Cumberlands. It was successful in a way, because it called a lot of official attention to poverty in the Appalachian coal fields. It brought the “war on poverty” to eastern Kentucky. But the officials understood poverty as a problem specifically of the people. They didn’t make the connection between the land and the people. So while the war on poverty was waged, the coal industry was tearing the land apart. And the result, of course, is that poverty persists in that region and so does the damage to the land.

The impulse to start a tobacco program may have begun with opposition to the Duke monopoly, the American Tobacco Company, back in the first decade of the twentieth century. The teens got a little better, but by the twenties we were in a farm depression again. The efforts to form a cooperative went on because, one after another, they failed. The growers would enter into an agreement to withhold the crop from the market until they could wedge a better price out of the buyers. The problem was that eventually some farmers had to have the money, little as it might be, and then that would destroy the cooperative.

The principle remedy was supplied by the federal government under the New Deal, and that was a “loan against the crop.” That loan against the crop enabled the warehouses to write a check to every seller, whether or not his crop was bought by a tobacco company. The tobacco companies had to pay a penny a pound above the support price to buy a crop. If nobody made that critical bid of a penny a pound more, then the cooperative took it—it “went to the pool” as they used to say at home—and it was marketed abroad.

The program employed both price supports and production controls. That was its virtue: it didn’t encourage overproduction as farm subsidies now do. The surpluses always work against the producer and always are a public gift—a tax payer’s gift—to the corporations. This cooperative program, among other things, provided exactly the same protection on the market to the small producers as to the large, and it made tobacco a staple crop—that is, a crop that farmers could rely on to produce a foreseeable income. And moreover—this is ironic—the crop, which finally became indefensible, you know, for reasons of health, had a very good effect on the land because it made a substantial income possible from a small acreage. Opponents of the program (or the crop) used to come forward with the idea that these farmers ought to grow corn. Well, to grow that much more corn would have ruined a lot of land. The fostering of one staple crop, however, was also a weakness in the program because it caused attention to gravitate to the staple crop, so in the long run it worked against diversity.

Under it all was the wish of the people who formed the cooperative program. My father was very much involved in the formation of that program and served in various capacities. He was president, for many years, of the Burley Tobacco Growers Cooperative Association. He and his friends were motivated by a wish to make a farm economy that was not a farmer killing economy. And that co-op did preserve the small farmers in my state for about sixty years. My dad used to say: “If you want people to love their country, let them own a little piece of it.” The idea was that from a reasonable acreage, a family ought to be able to live reasonably well. Not get rich, but have a substantial economic basis that would permit them to carry on and even to pass the farm along to the next generation. I knew the young men of that time—in the ’40s and ’50s—that my father was watching to remind himself of what he was working for. These were good, capable, intelligent, young (in those days, they’re all dead now) farmers, who were doing a good job farming—decent people—and maintaining their families with the help of the program.

There are two things about the program that stay with me. One is that it protected the small growers. The second is that it never for a minute separated the land and the people. My daughter, who is a farmer, realized that people in our region were talking as if the tobacco program were a thing of the past—they had forgotten it. So her work now is to preserve that idea and bring it back as a real possibility for a sensible farm economy. It would work for any farm product.

I was at the annual meeting of the Organic Valley co-op in Wisconsin last spring, and discovered to my great pleasure that the Organic Valley project grew straight out of the tobacco program: production control with price supports. It was organized by Wisconsin tobacco growers, among others.

CW: Your memories about your father’s work remind me of my own life. When I was growing up during the 1970s and ’80s, my father and uncle started a small metal fabrication company in the Pacific Northwest. I was around this company most of my life, at least until I went away to college. When I was too young to be of much use, I liked to wander around the shop and watch people work. There were light gauge welders and metal polishers—men who worked with what I now recognize to be a sense of artistry and practical skill. I liked to eat lunch with them and listen to their stories—watch their pranks—hear them laugh and tell jokes.

I bring this up because it is your emphasis on work, listening, memory— and really the joy mixed in with the struggle of work—that first attracted me to your novels. I’m thinking here about the people of Port William—Old Jack, Jayber Crow, Hannah Coulter—and your attention to the ways that they talk, their sense of vocation and artistry, and, really, their immeasurable value within a community. All of this is very moving to me. Even as a literary critic, who’s supposed to be distant from that sort of appreciation . . .

WB: Well, of course . . . [laughter]

CW: The way you talk about work, listening, and memory—particularly as practiced by earlier generations—describes a vision of sustainability that our culture now seems to neglect, or has just forgotten. I’m wondering if you have any thoughts on that.

WB: Well, I’m very moved by that time, that old way. First, because I loved it. Second, because it’s gone. Tobacco was a crop that involved a lot of hand work, hence, crew work, at the crucial times: the transplanting to the fields, sometimes even the weeding of the plant beds, the harvest, the preparation of the crop for market. At those times the talk went on, and it was wonderful talk. A writer couldn’t have had a better beginning, I think, than to have grown up in tobacco barns, and tobacco patches, and stripping rooms. Well, in the patch, you know, you’d maybe come to a time when everybody would sit down to rest—have a drink of water—and always the ability of conversation and storytelling to lighten the work was understood and appreciated.

I think the old tradition of work swapping, exchanges of labour among neighbours, was profoundly Christian. These people were not notably pious. Well, there wasn’t a lot of expurgation of their conversation [audience laughs]. But the rule was, for instance, that nobody is done until everybody is done. They stayed at it, they stayed with each other. And in the crew that I worked with, of neighbours and old friends, there was no accounting. Nobody ever got to the end and said, “I owe you two days” or “You owe me two days.”

I’ve attributed a brag to Danny Branch in the piece that I read yesterday, “The Branch Way of Doing,” that I lifted directly from a good friend and neighbour who said he’d worked on every farm on his road and had never earned a cent of money from it. He was proud of it. Well, I never heard that in church. Where I got that was from the people, and that was very moving. And that’s acknowledged now among the people who remember it—who went through it—as having been a good time. I ran into my neighbour at church a few Sundays ago . . . I go when it’s raining [audience laughs]. And I said, “Willy, when was the last year that I helped you cut tobacco?” And he said, “I don’t know, but you know I miss them old times.” But people paid attention to how they talked—to syntax. They didn’t know that word, but they knew how to load it, you know, so that a sentence would end with a snap, as it ought to [audience laughs].

CW: You are making me think about the relation ship between memory and time. Something that I really appreciate about your nov els is that you tend to write about the past and memory as still being with us in the present tense. This is one of my favourite aspects of your work. It really has everything to do with sustainability, although perhaps in a less tangible or measurable way. For example, when I was flying down here a couple days ago, I was re-reading Hannah Coulter. I came across a passage about the past and memory—it nearly brought tears to my eyes—and not wanting to become a basket case on the plane, I stopped right there. But I’d like to read the passage now and see if you might talk about it. It’s one of those moments where you . . . well, when I think about a passage of prose that is loaded up with a snap in it. This is one. So, this is from Hannah Coulter:

You think you will never forget any of this, you will remember it always just the way it was. But you can’t remember it the way it was. To know it, you have to be living in the presence of it right as it is happening. It can return only by surprise. Speaking of these things tells you that there are no words for them that are equal to them or that can restore them to your mind.

And so you have a life that you are living only now, now and now and now, gone before you can speak of it, and you must be thankful for living day by day, moment by moment, in this presence.

But you have a life too that you remember. It stays with you. You have lived a life in the breath and pulse and living light of the present, and your memories of it, remembered now, are of a different life in a different world and time. When you remember the past, you are not remembering it as it was. You are remembering it as it is. It is a vision or a dream, present with you in the present, alive with you in the only time you are alive. (HC [Berkeley: Counterpoint, 2004], 148)

I don’t know if you have anything to say about that, but that’s quite beautiful.

WB: Well, thank you. William Faulkner said pretty much the same thing, more briefly: The past is not past. My experience, that I suppose that comes from, is of living nearly all my life in the same place. I am very conscious—I’ve grown more conscious of it as I’ve grown older, and it’s very rich in my mind now—that every day I’m walking in the tracks and across the tracks of people I’ve loved, who are now up there on the hill in the graveyard. But they’re alive to me. It’s in the present that they live. This has caused me to think a lot about time, which, it seems to me, is as mysterious nearly as eternity. I think time verges off into eternity, when we are living actually in the present.

We live in the present only when we quit counting. If we start counting—the minutes, the hours, the days, the months, the years—we’re either living in the past, or we’re fantasizing—usually some horror story—about the future. It has amused me a lot in my dealings with scientists to argue that the present is uncountable. It has no duration . . . at all. If you get it down to nanoseconds, then there’s half a nanosecond. And then there’s half a half a nanosecond [laughs]. There isn’t any way you can measure it. If you start talking about it, it’s gone already. If I say “present,” it’s already past, you see. But if you’ve forgotten, if the thing you’re doing now makes you forget to count the time, it may be you’re in eternity: heaven or hell. But, anyway, those people of the past have a life. Mostly it survives by being remembered and loved, I think, and this is a very big thing in my life now. So that’s what I had on my mind. As Hannah ages, she realizes that her acquaintance among the dead has grown . . . and that happens [pause].

One thing I knew when Tanya and I decided to come home, to come to my home, was that I would help to bury a lot of people who couldn’t be replaced. And that’s happened. One of the great men of Port Royal used to say . . . he was a master mechanic who began learning his trade in a blacksmith shop and had come along with automobiles: “They’re going to be looking around for me, boy, when I’m up there on the hill.” He was a true prophet [audience laughter]. He’s never been replaced, never replaced. We’re looking around for him [laughs and then pauses].

CW: Well . . .

WB: Let me tell you something . . .

CW: Yes.

WB: That good man, the mechanic, had a garage in Port Royal. And I was still teaching at the university. I’d got it down to where I was going up there two days a week. And I didn’t want anybody to know it . . . especially him [laughs]. But one morning I got caught with an empty gas tank—I was dressed to go to school—and I had to go up there and pull up in front of his gas pump. He came out.

“Well,” he said, “You going up there to that university, boy?” [laughs]

And I said, “Yes sir, Mr. Lindsey.”

He said . . . [to audience] you know this is the kind of question you fear coming for the last hundred years . . .“How often you go up there, boy?” [laughs]

I said, “Two days a week, Mr. Lindsey.”

He said, “That ain’t what I call a job, boy. That’s what I call a position.” [audience laughs]

CW: That’s a good story [laughs] . . .

A couple of times in our conversation you’ve alluded to aspects of religion, which makes me think about some things you said yesterday about the Amish. You talked about the importance and centrality of religion as part of their existence together. This also makes me think about many conversations that you and Gary Snyder have had about religion in Distant Neighbors.

I’m thinking specifically about a letter that you wrote in 1980, when you were talking to Gary about your first attempts at writing what would become your early Sabbath poems. You talked about biblical words and ideas like resurrection, incarnation, and atonement—words that you tell him were part of your own local culture and, more broadly speaking, your Western cultural inheritance. And at one point you say this:

These poems are the result, partly, of a whole pattern of dissatisfactions: with my time and history, with my work, with my grasp of problems, with such solutions as I have found, with the traditions both of poetry and religion that the poems attempt to use and serve. That last dissatisfaction is the cause of all the immediate difficulties. There the traditions are, inextricably braided together, very beautiful in certain manifestations, but broken off, cheapened, weakened, encrusted with hateful growths—yet so rich, so full of the suggestion of usefulness and beauty, that I finally can’t resist the impulse to try to lay hold of them. (DN, [Berkeley: Counterpoint, 2014] 57)

As a person with similar feelings and concerns about biblical language—its many uses and misuses—I find what you say here to be of great importance. I’m wondering what possibilities for renewal you’ve found in your attempts to recover and utilize biblical language in your work over the years.

WB: Well, I was talking yesterday, in a piece I read from an essay called “Our Deserted Country,” about the economic value of intangibles. A lot of those intangibles are words that we’ve now distanced ourselves from by the superstition of objectivity. And by a deference to the materialism of the sciences—to what Wes Jackson and others have called “physics envy” [audience laughs]. So, we go about with a drastically foreshortened vocabulary, and a kind of apology for Milton, or Shakespeare, or George Herbert—as if they’re talking about things that concerned backward people in their time, which now can be approached only by way of the historical imagination, as if this is not language we can use now. This seems to me to be a great loss—a great loss to the humanities. The humanities ought to have stood their ground and claimed their territory and let these specializing vocabularies go to the devil.

We use that word “creative” and “creation” now, compulsively, and we apply it to everything [laughs]—but we don’t mean it. “Creative” comes from the language of religion. It’s a very important word, and now it may be the most abused word in the language.

I was recently asked if I would write a foreword to Liberty Hyde Bailey’s little book The Holy Earth. It will be a hundred years old next year. The Liberty Hyde Bailey Museum is going to publish a centennial edition. [Now published in paperback by Counterpoint.] Liberty Hyde Bailey was the dean of agriculture in his day at Cornell. And just for a mental exercise, ask yourself how many deans of agriculture in our time would title a book The Holy Earth. You see, he still had a whole language. Now that book raises some problems. It was written before the start of World War I, and he has some ideas about nature and progress that made a different kind of sense in his time than they can make now. So, I’ve got to walk a very careful path in talking about that book. But Liberty Hyde Bailey, if you look at his bibliography, wrote virtually a library all by himself. And a lot of those books or handbooks were on tree pruning, gardening—those things that were of interest to people who wished to make a household economy, a home economy. He was talking about home economics in a very literal way that had to do not just with housewifery in the modern sense, but with a reasonably self-sufficient home economy. That was a kind of wholeness, too, and his language came from that sense of wholeness. What that language does, of course, is admit into consideration those experiences, that we do have, that are not material [pause].

Life, for instance, the experience of life: who has been able to isolate life and study it by itself in a laboratory? You can’t do that. Aldo Leopold talked about seeing the light die in an old wolf’s eyes. If you’ve ever watched the death of a loved one or any animal, you know that there’s a light in the eyes that goes out at the moment of death. It’s like the difference between a dew-wet leaf and a leaf that is dry. Something happens that isn’t accountable. And if we’re going to talk about sustainability, we’ve got to include the unaccountable. I was talking yesterday about sympathy, imagination, familiarity—those things—that can’t be quantified. They can’t probably be studied. They can’t be euthanized and put into a vial and looked at [laughs]. They can’t be put on a slide and looked at under a microscope. But they’re real things.

Well, you know, I could go on and on about this . . . It has been pointed out to me that I’m an obsessed person [audience laughs].

CW: So many things that you just said remind me of when I read your essays for the first time. I was studying theology at Regent College at the University of British Columbia. During the first term that I was there, I read “The Gift of Good Land” and “Christianity and the Survival of Creation.” When I finished the essays, I remember thinking to myself: “Who is this Wendell Berry, and where has he been all my life?” I was so pleased to find another person who sees and responds to the world in a similar way as I do, at least in regard to aspects of Christianity.

What I’m saying, I guess, is that I appreciate how you’ve confronted and challenged many of the cultural misreadings and misuses of biblical ideas. In those two essays, for example, you address the perceived separation between body and soul, as well as the idea that heaven and earth are somehow vastly separated by a giant chasm. In your writings on body and soul, heaven and earth, these things are not separated, but intimately connected. I’m reminded, again, of Hannah Coulter, who mentions the hymn “In the Sweet By and By.” The song talks about gathering in a heavenly afterlife, a time when “we will meet on that beautiful shore.” But Hannah turns right around and says, “We all know what that beautiful shore is. It is Port William with all its loved ones come home alive.” I’ve heard you talk this way before, so I’m curious: What do you think of heaven, particularly the idea of heaven as a resurrected and transformed earth?

WB: I wrote about Hannah speaking of Port William in the hereafter, and Port William adorned as a bride [pause].

There are limits to the human imagination, and when the human has sat down and tried to imagine heaven, it’s always a bore [audience laughs]. Mark Twain said, “Heaven for climate, hell for company” [audience laughs]. So, what we know of heaven, it seems to me, we’re learning on earth. And we do use that adjective “heavenly.” We throw it around a bit too much, but in the large economy of this existence of ours there is a generosity, and very good things happen to us that make us forget for a while that we’re living in time. If we have good work to do, that can make it happen. Love can make it happen. Art can make it happen. Sleep even, on a good night, can make it happen. So, I’m talking to you now the way I talk to myself.

This business of healing that dualism—that divorce—between the so-called “material” and the so-called “spiritual” is something I think I’ve not handled except clumsily. Nevertheless, that split, that divorce of the soul from the body, heaven from earth, creator from creation, has caused a lot of harm. As soon as you make that division—this is historically true, I think—when you make that divorce, one gets to be higher than the other, and then the lower begins to be sacrificed to the higher. I heard a lot of sermons when I was growing up, in which the body’s life in this world, along with this world, were looked upon as perishable, corrupt, material things that were to be despised and traded off eventually for heaven. You can see the economic paradigm, so to speak, that intrudes, then, into that space between the divided principles of spirit and matter. Matter, divorced from “higher” value, is readily destroyed for money. And we think—we literate, sophisticated people—that that dichotomy is a superstition being carried on by the fundamentalists, a thing of the past.

But we don’t get off that easily. When you start the departmentalizing of intellectual life, the life of the mind, the dualism continues.

It becomes the divorce between mind and matter. People give over the material world to the management of the materialists who turn it into cash just as quickly as they can. So you get surface mining—which is just unimaginably violent. You get ways of farming that are equally violent, if slower. You get chemical pollution of the waterways, of the rain itself, of the water cycle. You get soil erosion. You get the destruction of the rural communities, of such as we ever had of cultures of husbandry, which were sometimes pretty good, sometimes not.

I came up under my father, which was a difficulty in a lot of ways, because he was demanding. But he could be tender, too. One of the things he was tender toward always, always, was the land. I remember him saying over and over again, “This land responds to good treatment.” His purpose was to treat it well. By treating it well, he meant keeping it covered with grass. And he used an interesting metaphor. He’d talk about a gulley that had been healed, and he would say, “It’s haired over.” He was comparing the gulley or the gall on the land to a harness gall on a horse. Healed and haired over. He saw that land as a living thing, you see. So when I first saw, in 1965, the dozers opening a cut for a strip mine on a mountainside in eastern Kentucky, I was shocked. I had thought that my father’s attitude toward the land was the norm. The idea that somebody could go at the surface of it and utterly destroy it! The surface of it, you know, is what we live from. That’s what keeps us alive.

CW: One of the things you said near the beginning of that response might be the sign of a first argument between us [laughs].

WB: All right, let’s have it.

CW: No, only because you were dismissive of yourself. You said that you’ve handled these issues of dualism rather clumsily—not well at all. I think you’ve done as well as about anyone I’ve read.

WB: Well, that’s not saying much [audience laughs].

CW: Come on! [both laugh]

WB: I think, you see, what we’re confronting is the failure of materialism. Industrial agriculture is in an advanced state of failure. There is that hypoxic zone in the Gulf of Mexico. There is universal pollution of the rural waters. Glyphosate and its decayed versions contaminate a lot of rivers in the Midwest. Wes Jackson sent me a warning from a motel in eastern Colorado to pregnant women, children, and others who mustn’t drink the local water because of agricultural pollution. So we’re living with this failure.

The failure is in medicine, too. In the last few years, I’ve become increasingly acquainted with doctors, who are trying to confront the failure of industrial medicine, which is the failure to recognize the creatureliness of patients. Their uniqueness as individual persons. The machinery that they attach you to when you go to the hospital is not capable of making such distinctions. So these doctors are trying to strain against that—and that is clumsy, too. I think the people who recognize this failure are involved in a kind of clumsiness that will be with us for a while.

You know, I can write a fairly good sentence, but that doesn’t mean my handling of this problem is better than clumsy. I have to suppose that we’re early in the game and that later—if things go as we would like them to—people will say, “Well, he was doing his best . . .” [laughs].

CW: I’ll take that as an answer. I can live with that [both laugh].

I also want to bring up a passage by Gary Snyder. He is the other voice in Distant Neighbors and has so many important things to say. At one point in the letters, you and Gary talk about your poem “For the Hog Killing” and his essay “Grace,” which became part of a longer essay called “Survival and Sacrament” in The Practice of the Wild.

During this exchange you talk about issues such as prayer, gratitude, and our creaturely need to take life in order to sustain our own lives—and that ongoing tension. I think it’s one of the most important parts of the book because it deals with something that a lot of people are thinking about. I just want to read you a passage from Gary’s essay that you responded to in the letters—and then see what you have to say about it. This is from Gary Snyder’s essay “Survival and Sacrament”:

Everyone who ever lived took the lives of other animals, pulled plants, plucked fruit, and ate. Primary people have had their own ways of trying to understand the precept of nonharming. They knew that taking life required gratitude and care. There is no death that is not somebody’s food, no life that is not somebody’s death. Some would take this as a sign that the universe is fundamentally flawed. This leads to a disgust with self, with humanity, and with nature. Otherworldly philosophies end up doing more damage to the planet (and human psyches) than the pain and suffering that is in the existential conditions they seek to transcend.

Then, a bit later, he says this:

A subsistence economy is a sacramental economy because it has faced up to one of the critical problems of life and death: the taking of life for food. (PW [New York: North Point, 1990], 183–84)

I’m just wondering what you think about that. How do these thoughts resonate with you?

WB: Gary Snyder’s Buddhism, his values that are worked out carefully by his scholarship and study, all that makes him sympathetic to a lot of us countercultural types. Underneath that is the willingness to confront reality and tell the truth. What he says about us living inescapably at the expense of other lives is true. You can’t escape it by being a vegetarian, or vegan, or whatever. There’s no escape. If you sit here eating vegetables, you’re taking up room, in which other creatures could have lived if you weren’t occupying the space.

So the issue moves away from a kind of abstinence, or a kind of misanthropy, toward the question of the respect these other lives require of you. Or what might be the proper reparation, or even expiation, toward these fellow creatures by whose deaths we live. Here again, I think, we in our culture are at the beginning. Later, we have to hope and pray that people will get better at it—that they will know a little more securely how to convey this respect.

What brought that into Gary’s and my correspondence was my poem “For the Hog Killing,” which is a kind of prayer:

Let them stand still for the bullet, and stare the shooter in the eye,

. . . let them die as they fall.

Well, that comes from another thing that we neighbours used to do together every year—that was kill hogs. Sometimes we’d do two very big days’ work, maybe we’d kill fifteen. The rule, for the shooter, always was: “Never make ’em squeal.” There was a man named Marvin Ford among us who never made one squeal. He was left handed, which made his shooting always a little awkward-looking—made it always subject to study in a way—because of its oddity. He held his rifle, you know, in his hands like this [shows audience]. And he would be moving around as the hog would be moving around. What he was waiting for was for the hog to lift his head and look straight at him. And then he knew exactly where to put the shot. The hog would fall without a sound. And there would be people standing there ready to grab him by the forelegs, turn him on his back, and stick him—and it was over.

That was what we owed. It’s not an easy thing to kill an animal you’ve looked after and fed, that you’ve committed yourself to care for. That was understood. We weren’t killing fifteen out of a thousand head. All of us knew, more or less, that these hogs had been lived with by some of us. So there it is, in, you may think, a rather primitive state. But that was it, and that was what I was writing about. The whole thing was conducted on principles, not stated, but the head man among us used to start the day by saying, “If it’s anything I hate, it’s a nasty damned hog killing.” Then everybody was on alert, you know. Get it right. Keep the dirt out of it. We did a good job.

CW: Most of the people here today are educators of some sort, perhaps teaching courses in the humanities in regard to ecology and place. One of the challenges I run into when teaching such courses is that the material and conversation can turn, well, let’s just say, apocalyptic and depressing in a hurry. Since I don’t like to take that path, I’m curious as you travel around and meet young people in Kentucky and beyond, what are some of the things that bring you hope in a time when it has become so easy, convenient, and maybe even pleasurable for people to despair?

WB: This is what Wes Jackson calls the “ain’t it awful conversation” [audience laughs]. One of the mental strategies of dealing with this business of sustainability is to find a way out by conversation—the way out of the “ain’t it awful conversation”—into some kind of careful, exact definition of the problems we have. That is the way it begins, and it gives the trajectory. If you can get an accurate enough description of a problem, you’re well on your way to getting it solved. So we have to hope.

I’m worrying a lot about climate change because it’s the name of a whole set of problems. Wastefulness, for instance, and toxicity. If we could solve our problem of wastefulness, we’d go a long way toward solving the problem of climate change. Same for our chemical addictions. There are eighty-five thousand chemicals on the loose among us, to help us live better—you remember “Better Living through Chemistry”? Eighty-five thousand chemicals, and they’re all winding up in the streams, of course, and the Environmental Protection Agency has studied two hundred of them.

Anyway, to get from the “ain’t it awful conversation,” I think you’ve got to go through the problems. I’m seeing a lot of young people who understand that—that we have problems that are definable in a way that leads to work. “Climate change” has a way of leading to insistence on policy changes, as if only the governments are going to save us, when really it’s going to be radical changes of behaviour, or of conduct. So that gives me hope—the young people paying attention to the problems. Sometimes you find young people who’ve already made a commitment to some kind of good work that they can actually do. And that’s hope giving. Sometimes the young people know older people who are actually at work on problems they can actually work at. And that’s hope giving. Hope is difficult. But it’s a virtue, you know. It’s required.

I want to distinguish, then, between hope and optimism. Optimism is a program that says, “Everything is going to turn out all right.” And that lets you out, you see. Pessimism is just as good, “Everything is going to turn out bad. There’s nothing you can do about it, so come to rest. Watch television.” Hope doesn’t accept those limits. Hope may even say, “Down the road we’re going to have some fun. We’re going to get together and work together. We’re going to talk—tell a few jokes. We’re going to have some good surprises, even.”

If you know the history of the conservation effort, you know there have been some victories. Even in Kentucky we’ve had some. We beat the Red River Gorge Dam. We beat the Eagle Lake Dam twice. We beat the Louisville International Airport. We stopped the Marble Hill Nuclear Power Plant on the Indiana side of the Ohio River. So these things have happened. But there’s also discouragement. Farming has gotten worse. The planted acreage has gotten larger, the machinery bigger, the indebtedness—much worse. The chemicals are more powerful and dangerous. We haven’t succeeded at all in stopping strip mining. The coal companies have just done what they wanted to. I wrote about this in a written interview for The American Conservative: in Kentucky, all the politicians of both parties have been eaten, digested, and shat by the coal industry. That’s discouraging [audience laughs]. But you have to be grateful for small things. Sometimes I’m reduced just to the butterflies and the flowers. Sometimes I do better.

CW: All right. We can take a few questions from the audience, if anyone has any.

WB: But we have been talking about sustainability, now . . . that’s been the subject.

AUD: Thank you. It’s been really wonderful to hear your words today. Earlier you talked about homecoming and its relationship to death and loss. I wonder how you think our current cultural discomfort with death contributes to that problem, or is symptomatic of a loss of home. Could you talk further about that idea?

WB: Well, there’s a lot involved there [pause] . . .

CW: I remember you writing about the need for Western culture to confront death in your essay “Discipline and Hope” . . .

WB: Well, that was back when I was smart [audience laughs]. Death and hope . . . I’m old enough now to begin to understand death as a problem solver [laughs]. It’s the only good excuse. There are some things that keep you involved, you know, but if you say, “I’m sorry, I’m dead . . .” [audience laughs]

Wes Jackson talked about the two majors: the major in upward mobility and the major in homecoming. He said, up until now the only major has been upward mobility; now we’ve got to have a major in homecoming. Well, I think, living at home among people you know for a long time, seeing the generations come and go, you begin to understand that death has its place, and it’s an honorable place and a very bearable one.

Francis Collins, a Christian who worked on the Human Genome Project, is still caught in the progressive mythology, or superstition. He is predicting that we could live 140 years. Well, 140 years is too many—if you’ve been around a while, if you’ve spent a proper amount of time at the funeral home. The question you finally come to at my age is, How many wars do you want to live through? How many times do you want to go and take the hands, or put your arm around members of a family who’ve lost a child? And then say the most inadequate thing you can say, “I’m sorry.” How much of that do you want?

I think that mobility keeps us from dealing with this problem. I think there are people living now who’ve rarely or never been to the funeral home, who’ve never seen a dead person. If you live in a little old perishing country community, in a perishing rural county, like I do, you see a lot of that. You realize that there will come a time when enough will be enough. My granddaddy said to one of his daughters-in-law, one time—she’d taken him to a funeral— “One of these days, I’m going to go to one too many of these.” [laughs with audience]

The medical industry is always telling us how much they’ve increased longevity, but that’s a very misleading statistic because sometimes they increase longevity by keeping people alive who really ought not to be alive—who don’t know who they are anymore, who are incapable of any pleasure anymore, and so on.

AUD: I really appreciated when you were talking about present time merging with eternity. It makes me think of the “rememberers” in Port William—Burley Coulter, Jayber Crow—the people who know the memories of the people they never met because they’ve lived in the place. Who else is writing now that you feel is in that tradition? Maurice Manning comes to mind with his collection The Gone and the Going Away. Maybe it’s no coincidence that he’s a farmer, too. But who else do you see as a “rememberer” who is writing now?

WB: I’ve known Maurice since he was a student, and I know that Maurice has taken responsibility as a person who knows much of his own history and inheritance. Yes, Maurice is one of them. There are others of his generation. Donald Hall in my own is one, because he went back to live in his grandparents’ house that he visited as a boy. So he’s got that inheritance, really very substantially, in his attic. He has a bone ring that one of his great-grandfathers brought back from the Civil War, highchairs that his mother and aunt sat in, a bit of fleece that somebody in the family carded and put away and never got out to spin. So Don is one of those, and we’ve been friends a long time. I know how that lies on his mind, how he goes over and over it. And we have the example of Faulkner, in an older generation; William Carlos Williams in the same generation, who lived all his life in the house he was born in—in Rutherford, New Jersey.

Well that’s the kind of question that will lead me to think, at three o’clock in the morning, about somebody I should have mentioned. There are people who have made themselves responsible for memory. History is written, but as John Lukacs says, it’s also remembered. Imperfectly, don’t forget, and incompletely.

AUD: I’m wondering about your views on education. I was reading Hannah Coulter again, and I thought, “Wendell Berry has some views about education that are not flattering.” I think I understand your critique. But if we could do one thing in the university, what is the one place that we should start in re-thinking our values and our organization?

WB: Well, you know my bias. I think one way to do that would be to start locally. This is one of the telephone fantasies that Wes Jackson and I have carried on at great length. Suppose a university, as a body of scholars, addressed itself to questions like, What’s going on here? What was here before we came? What has happened here? What’s the accounting on gains and losses? What should be happening to address the losses and to affirm and strengthen the gains?

What tickles me about those questions is that they can’t be answered in a department. First thing you know, you’d have to call in an ecologist—you’d have to have a forest ecologist, or you might have to have a prairie ecologist. You’d need a chemist—very soon. You’d need a geologist. You might even have to call in somebody from the English department to deal with stories and poems, or stories and songs. In my part of the country, you’d certainly have to have a musician, to talk about the local traditions of fiddling. That could start a conversation between the members of the faculty, but also among the members of the faculty and their students—that could go on for generation after generation. It would be a fascinating conversation because it would bring the disciplines into conversation with each other. And it would revolutionize the language of the disciplines because they would have to talk to each other, which would mean that they would have to help each other to understand each other’s language. So it would renew the principle of cooperation.

In these local attempts to have local food economies, what we’re really trying to do is change the script, from competition to cooperation and neighbourliness, assuming that in cooperation we can come upon solutions and transactions that can help both parties. As it is, I’m afraid the universities are really working to keep things from being found out. Wes Jackson told me one time—he’d just been to some great university—“I walked around and I looked. They had these classrooms, well-equipped with black-boards and so on, a library well furnished with books. They had laboratories, well-equipped. And I said to myself, ‘This would be a hell of a good place to have a school!’” [audience laughs with WB]

Well, I’ve felt like that sometimes, I must say.

AUD: The talk about Gary Snyder made me think of a question regarding an aspect of literary history. It involves you, and writers like Ed McClanahan, and Gurney Norman, and possibly even Hunter Thompson. There seems to be this Kentucky contingent in the countercultural literature of the 1960s. They found themselves out on the West Coast. I’ve always been intrigued by this. What were these writers doing there? And how did they end up there? And how did they contribute to that particular culture?

WB: On the West Coast?

AUD: Yes.

WB: Whew. Well, a variety of things they were doing out there [audience laughs]. If you know Gurney’s novel Divine Right’s Trip, you know how carefully he had tried to build a bridge from the West Coast counterculture to what was going on in Hazard, or Perry County, in Kentucky. Ed, in his way, has tried to do that—sometimes in very funny essays. Gurney, Ed, Jim Hall—we were friends in both Kentucky and California.

When I went out there, I was a little earlier—the counterculture hadn’t really started when I first went to Stanford. But it was kind of a breathtaking time for me. I’d never been west of Missouri. So I saw the West for the first time. I was with my wife, Tanya Berry, who was raised in Mill Valley, California, or partly so, although her family are mostly from Kentucky. Then I was in the seminar at Stanford. Nancy Packer was in that seminar, who just won an award from The Sewanee Review for a short story. Ken Kesey was in that seminar and Ken Babbs. And Ernest J. Gaines was in that seminar. The seminar was taught by two wonderful people, Wallace Stegner being one of them, and that began my acquaintance with Wallace Stegner, who didn’t influence me as much then as he did later. Ed Abbey had just been there. Larry McMurtry was coming, along with Ed, and Jim, and Gurney.

So, maybe what that West Coast experience did for us was make us a little less provincial and a little more parochial—to use Patrick Kavanagh terms. Patrick Kavanagh said that provincials are always looking over their shoulders, to see if people think they’re provincial. In Kentucky the provincials are always looking to make sure their shoes are on. The parochial writer is convinced of the imaginative sufficiency of his or her place. [audience applauds]

WB: Well, thank you for being an audience that is pleasing to talk to. I felt like I ought to say something good in here—maybe I did a time or two.

CW: Wendell Berry, you’ve given us more than fifty years of thoughtful and imaginative writing about living with deliberate care. I want to thank you for that. But based on the brief time that I’ve gotten to know you, I also want to say that even if you hadn’t written any of it, you would still be someone that I would want to spend some time with and get to know. Thank you for being the way you are. Blessings to you and your work.

WB: Well, thank you very much . . . When people praise me, I always think of Tanya [laughs]. We had some company at lunch one day. They got started on giving me credit. And I finally had all of it I could stand. And I said, “You’re giving me too much credit. I’m just a kind of low-life.” And Tanya said . . . [laughs and nods head up and down].

[audience applauds with laughter]

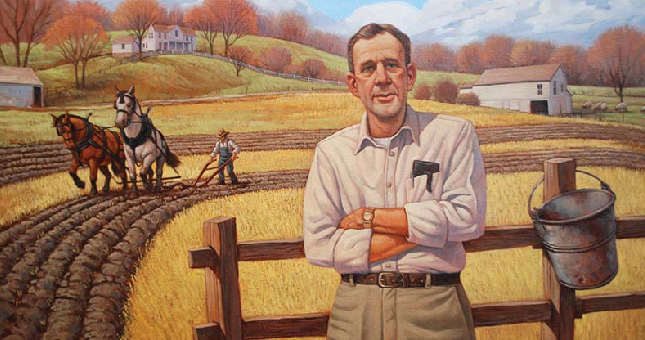

Photo credit: Wendell Berry